Trends and outlook for airports: Continued change in business models in 2016

As the year turns, the outlook continues bright for airlines as they prosper from a continuing stagnation in oil prices on the cost side and rapidly building demand in most of the world's regions, with only the cargo segment disappointing. As margins touch 6% they are at the top end of a cycle the likes of which has not been seen for four decades. While this is bound to bring benefits for airports, for the first time airport infrastructure is actually looking to be less of a gambling certainty than are the airlines.

Cycles cannot last forever of course and this one will not. While oil prices may remain stable at a low level for some time (the oil companies have catered for that in their forward planning) there are few genuine shining lights in the global economy and too many concerns, of which China is just one.

The world economy is expected to expand by 3.1% in 2015, down 2 ppts from the previous forecast of 3.3%, representing the slowest expansion rate since 2009, when global growth ground to a halt. It is expected to improve in 2016 to 3.6% but that is already less than the previous forecast and subject to further potential downward revision. The International Monetary Fund is of the opinion that the probability of recession has increased across much of the developed and emerging world.

But the airport business is determined by bricks and mortar, tarmac, steel and glass and the longevity that goes with it - not by easily leasable, portable and disposable lumps of aluminium or carbon composites. Irrespective of the macroeconomic projections for the performance of economies, as long as IATA carries on saying that there will be 4.1% average growth in demand over the next 20 years, thereby more than doubling 2014's number of passengers (3.3 billion to over 7 billion) then there will be investors prepared to put their money into runways and terminals.

Yet, while the number of private sector investors is growing, that can, surprisingly, be a bad thing for airport investment. As UK Airports Commission Chief Sir Howard Davies said during his long-awaited recommendation for the next southeast England runway, private investors tend to wait for additional demand to materialise rather than to anticipate it; it is governments and municipalities who often deliver infrastructure faster, even if the decision is determined more by hope than by reality. And nowhere is that truer than in the UK itself, where almost every airport is at least corporatised, and most have private sector investors. It is where the only new full length runway at an existing primary commercial airport since the Second World War was delivered in 2001 by what was then a wholly public sector enterprise. That was Manchester Airport, just eight years after the initial application, and mainly self funded.

There are various ways of measuring the "privatisation" of the airports industry. One of those measures has it that around 15% of airports globally are in fully private ownership, about 18% are public private partnerships (PPPs) of one sort or another and the rest (67%) remain in full public ownership. (There are occasional examples of reverse privatisations but not so many as to merit consideration here). But another measure has it that 50% of passengers now travel through fully privatised or commercialised airports. This indicates that privatised airports are still mainly primary ones, or at least those secondary ones that are not entirely dependent on low cost carriers.

For those in the former category, 2016 looks rosy as they are the most likely to benefit both from the upturn in the airline sector and from investment. Right now that type of airport compares well with other non-aviation industry sectors from the point of view of risk and of investment return. They offer opportunities for aeronautical revenue growth, diversification into and via other revenue streams, and the greater flexibility to respond to changing circumstances that arises naturally from their size and scope. That omnipotent bugbear, airline fragility, is hardly a thing of the past but right now it is less visible than it was.

Take for example 3Q 2015 passenger figures from ACI Europe, which reported growth in all of its four categories as follows: >25 million ppa +5%; 10-25 million ppa +7.6%; 5-10 million ppa +6.2%; and <5 million ppa +7.4% for an overall average of +6.55%. But amongst the best 16 performers, four from each category, there was not a single airport that could be classed as secondary or tertiary and the majority of them act as hubs to a greater or lesser degree.

For those airports in the latter category 2016 will also be better - known and unknowns permitting - and the 3Q2015 figures above for airports in the <5 million ppa category lend support to that statement. But it will still be the case in many countries which depend on budget airlines that there will not be the rapid growth of routes they became accustomed to prior to 2008.

Neither will they be able to attract full service carriers (FSCs) away from primary airports in large numbers, or develop new FSC routes, or see their regional airlines doing anything other than to continue to struggle to justify some of their routes.

Well not yet, anyway. Later in 2016 or 2017 could be significantly better, all things being equal.

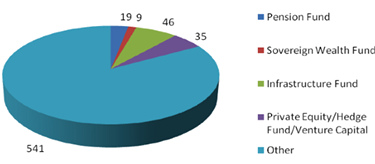

Irrespective of their preference for primary airports the number of airport investors continues to grow. As of Nov-2015 the CAPA Global Airport Investors Database has 650 corporate entries and it is expected to expand to over 700 by Dec-2016. They encompass the full gamut of organisations from one man investors to sovereign wealth funds; but the most noticeable increase continues to be in the number of funds generally (pension, investment, hedge, private equity, sovereign wealth etc) and again this is expected to continue.

Gone are the days when airport investors were mainly bus and train operators or property developers hankering after the main chance.

The table below identifies how many of the different fund types there now are out of the overall total of 650.

It is useful to compare this data with the same period in Nov-2014, when there were 546 known investors. While that overall figure has risen by 19%, the biggest increase in 12 months has been in infrastructure funds (+31.5%). Pension Funds and private equity concerns involved in airport privatisation increased by roughly the same as the overall figure while just one more sovereign wealth fund was added to the database.

The other noticeable increase has been in the number and range of public private partnership (PPP) transactions worldwide, which is expected to continue. While the retraction of the offer of PPP contracts for Chennai and Kolkata airports in India might not have dealt a fatal blow to future PPP deals there it has certainly set them back.

But elsewhere in the world they are becoming increasingly popular for a variety of reasons, and not least in the US where a PPP transaction was successfully concluded earlier in 2015 to build and operate a new Central Terminal at New York's La Guardia Airport. There are numerous other projects under consideration in the US arising from the successful closure of that one: at Des Moines, Idaho for example.

The PPP is often more attractive to governments because they can retain a greater degree of control from what is often constructed as a form of lease in which projects can be delivered on time and within budget, at the same time generating attractive risk adjusted returns for private investors.

For those investors, in 2016 opportunities will arise in Japan (upon the successful completion of the Osaka Airports concession deal which is being concluded in late-2015); in Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, which includes an IPO on the Airports Corporation itself); in Russia; in Iran, which is still heavily state controlled but which has an infrastructure gap to fill quickly, once sanctions are lifted; and in Latin American countries such as Colombia.

In Europe, France will probably move to privatise more primary airports once the Lyon and Nice deals are wrapped up. The successful privatisation of 14 Greek regional airports may open the way at last for an IPO on Athens Airport, or if not for a further sale to the trade of the government's stake. Also in Italy, though the main airports there are already privatised. In Eastern Europe it is mainly less attractive secondary level airports where the private sector is coveted but Sofia Airport will be subject to a concession offer and private management is sought at Lithuanian Airports.

|

Airport investors by type, focus on funds

|

The number of building projects at existing airports continues to rise. As of mid Nov-2015 the CAPA Airport Construction Database records 2571 construction projects at existing airports, over 200 more than at this time last year. The greatest number (791) is in Europe.

But only 144 of them (18%) are in the 'critical' categories of new or extended runway; or new or expanded terminal. Compare that with Asia Pacific, where 48.6% (316) of the 650 known projects fall into those four critical categories. ('Other' projects can be anything from apron and taxiway reconstruction, to a new ATC tower or administrative building, or, at the other end of the scale, an airport city - see left.)

"Low cost airport" projects, usually a simple terminal, currently total 18 worldwide, of which the majority (nine) are in Asia Pacific. Nearly 60% of seats in Southeast Asia and a fast growing proportion in North Asia are on LCCs, on whom much of the future growth is expected, this is perhaps to be expected. Unlike Europe, attracting and keeping LCCs is the prize in Asia, as full service airlines change tack.

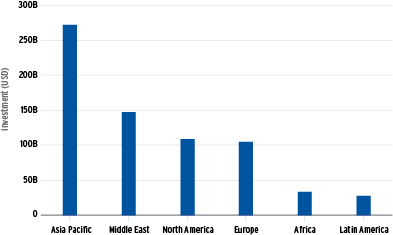

The total value of all these projects, which include those already under way as well those about to start or planned, runs to USD682.5 billion, and with USD262.4 billion (38.4%) of it taking place in Asia Pacific.

|

Airport Construction Investment - activity by region (USD)

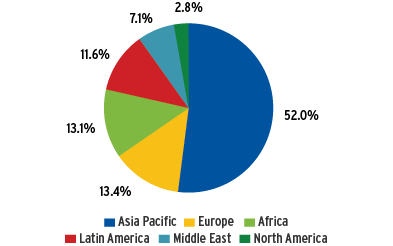

Number of new airport projects by region, DEC-2015

|

The number of new, green or brown-field airports under construction or in the planning stage also continues to increase. In Dec-2014 in Asia there were almost four times as many (199) as in second placed Europe. Africa is only just behind Europe in this category. There has been hardly any increase in new build airports in North America during the last 12 months; up from seven to 10.

The total value of these global new airport projects is fractionally over USD200 billion, of which, again, Asia Pacific accounts for the majority (45.7%).

There is no evident reason why construction activities overall should not continue at this pace through 2016. Almost all airport infrastructure is instigated with a view to the long term, and usually irrespective of short term events or mid term 'shocks,' and while construction in regions where air travel is more mature may stabilise that will not be the case in most of Asia Pacific, also Russia, Africa and parts of Latin America.

While the focus in aviation continues to shift towards affordability and 'democratisation', the demands of low cost airlines will continue to dictate the pace and direction of airport investment, and not only at secondary level airports and in emerging economies.

To offer just one example, London Gatwick Airport, which in late 2015 still aspired to getting UK government approval for a second runway - rather than for a third one at Heathrow Airport - (and which has stated it will build one anyway, irrespective of that decision) is currently investing GBP1 billion (USD1.52 billion) in infrastructure upgrades. Much of it is on facilities that will ease both the journeys and operational connectivity of passengers using LCCs.

Apart from the enormous presence of easyJet, the Norwegian Group, which already has six trans-Atlantic routes there and 10 based aircraft, has received a UK operating licence, thus opening up potential bilateral operating rights for its low cost flights to new markets such as Asia, South America and South Africa. Meanwhile the Canadian LCC WestJet begins its own six city trans-Atlantic flight series at Gatwick in 2016.

It is a reasonable assumption that similar developments will take place at primary airports elsewhere, with the same impact on construction investment decisions.

The need for additional capacity is what drives construction. CAPA has stated in the past that actual or imminent capacity crises in some parts of the world may be overstated. It is a crisis when a passenger simply cannot get to a business meeting, or a wedding, or to the scene of incident involving relatives or friends because there are no seats to be had at all, but that rarely happens.

There is one region which is genuinely facing such a crisis though: the Middle East. In that case however the problem is not so much one of insufficient airport capacity - the three main hubs have got or are getting a new airport or additional terminal facilities and other airports like Bahrain and Kuwait are being expanded considerably - as of congested air space (although it should be borne in mind that the world's sixth busiest airport in 2014 (and third busiest as of 1Q2015) Dubai International - has only two runways).

The congestion is brought about mainly by additional and ever growing military activity in the region - over 50% of the airspace in the Middle East is reserved for military flights even before the newly declared 'war on ISIS' is taken into account. But there are other issues, such as dated air traffic control systems, the snail-like progress towards a Single Sky control mechanism (though Europe is hardly in a position to complain about that, even if it wanted to), and in some cases less than optimal use of runways.

The Middle East, and especially the Gulf, is a globally strategic location with significant transit volumes of air traffic; a destination in its own right and a crossroads between Africa, Asia and Europe. If there is one infrastructure 'crisis' that needs sorting out urgently, this is it.

The importance of non-aeronautical revenue streams will continue in 2016. While it is entirely possible in the short term that secondary level airports may be able justifiably to demand higher charges from ULCCs (ultra low cost carriers) and LCCs if oil prices continue to be suppressed, all airports must accept that the role of Principal Customer is shifting away from the airlines towards the passenger, just as Ryanair CEO Michael O'Leary continues to perceive his ultimate goal for the carrier is to have ticket prices at zero, with the airline supporting itself through the sale of snacks, WiFi and in-flight entertainment.

There are other alternatives of course and many airports have become extremely innovative and adept at finding new ways of generating income that have little or no connection to the presence of aircraft. But the volume revenue potential of such innovations remains comparatively low and in the immediate future shops, stores, bars, restaurants and car parking will continue to prevail.

At the other end of the scale from the budget terminal or airport and airport shopping there is an impact from the growing numbers of airport cities, aerotropolises and other such enterprises. There are already close to 100 formally academically recognised aerotropolises worldwide (i.e. the extended area around an airport city) and there are over 50 airport cities in China alone.

As metropolitan areas continue to converge in many countries into megalopolises, the economies of cities will depend more on their airports and vice versa, which also impacts on the 'economic multiplier' effect on employment. A shift is likely to take place in many city regions in which the majority of well-paid employment will increasingly gravitate towards the location of the airport, at the expense of other suburbs, and with all the social upheaval that brings.

In this instance the very essence of what an airport is and what is stands for is about to change and there is no way of knowing how that change will be accommodated and accepted sociologically.

Last but not least is the question of the environment. With dark and foreboding warnings about impending and dramatic climate change, the aviation industry as a whole will continue to play its part in tackling such change, even if it is a relatively insignificant contributor to it and if, indeed, it exists at all. Not everyone is a believer.

One of the most likely manifestations of environmental awareness will be in the form of installations of solar panels. Already 100 airports have invested in solar energy and one airport in India, Cochin, covers 100% of its power costs in this manner.

There are several reasons why solar power will continue to be popular. First, it is not necessarily a cost item. It is possible with even a medium sized installation to generate sufficient power to light a terminal, or a runway, and still be able to generate some cash as well by feeding excess power into the local or national grid or even selling it to a privatised power company. Secondly, governments like it (although the appeal of alternative energy is diminishing in some countries) and may underwrite its installation or maintenance.

Thirdly, it is so manifest. A passenger, or even a passer-by, cannot help but notice a shiny solar panel installation on a terminal or car park roof, or on spare land. That makes for good PR, much better than a new de-icing run-off facility; or a bicycle or pedestrian path or planting a few trees, which are unlikely to be noticed.

In conclusion, the business model of airports has changed and continues to do so. Airports have moved away from being mere infrastructure providers to fully fledged and diversified businesses. Adapting to this new paradigm will keep airport management on its toes throughout the coming year and well into the future.