Europe-Asia appears likely to be a truly innovative and world changing market

Air traffic between Europe and Asia has achieved consistently moderate growth, unlike the high speed to rapid expansion between Asia and North America.

Yet, with the exception of a handful of smaller airlines with niche connecting opportunities, like Finnair and LOT (and Norwegian), the potential for organic growth is limited. JVs are gradually becoming more common, bringing opportunities but also challenges as they overlap, due to the convergence of the European-Asian market.

It has in effect been two markets, one segment from Europe to Northeast Asia and another Europe to Southeast Asia. With a few exceptions, neither region acted as a hub for the other, in contrast to Asia-North America or North America-Europe, where the geography of each region is sufficiently close that European airports can be a hub for the region. Northeast Asia is however a hub for Southeast Asian traffic to/from North America.

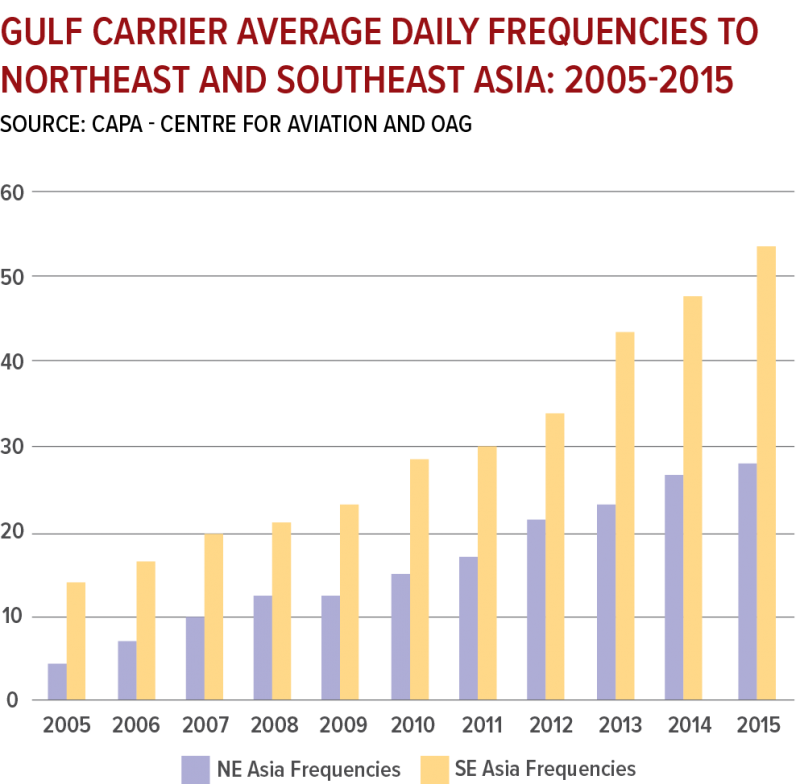

The convergence of Asian flows to Europe has been underlined by Gulf airlines in the south and mostly Chinese airlines in the north. Because of their geography, Gulf airlines have only moderately circuitous connections between Southeast Asia and Europe. The local market has adapted quickly to travel on the Gulf airlines. Northeast Asia is more difficult. The more northern geography of the region means greater circuitry is introduced to European connections, with the backtracking highest for the prime markets like Beijing, Seoul and Tokyo.

The Japanese market is mostly focussed on saving time and has a strong preference for using Japanese airlines. Korea has been frugal with traffic rights, leaving the Gulf airlines with a single daily flight each. There are however some signs of optimism in China for Gulf airlines - Emirates especially - given the Chinese government's top-level initiative to be linked to the Middle East.

On northern routes, Chinese airlines are increasingly imposing their stamp on Europe traffic flows, wresting back market share from airlines and hubs that fed off their market while Chinese airlines were under-represented. They now have the opportunity themselves to become hub airlines, for example replacing Seoul Incheon's role as a hub for Japanese-Europe traffic. Mainland Chinese airlines already have an established position in the Taiwan-Europe market.

Some Chinese hubs will also be favourable for Southeast Asian connections. Backtracking and connections may be disadvantageous, but the lower cost base of Chinese airlines and their available capacity can place favourable fares on the market. Some emerging hubs, like Kunming, expect their intercontinental forte, even if small for a while, to be between Europe and Southeast Asia.

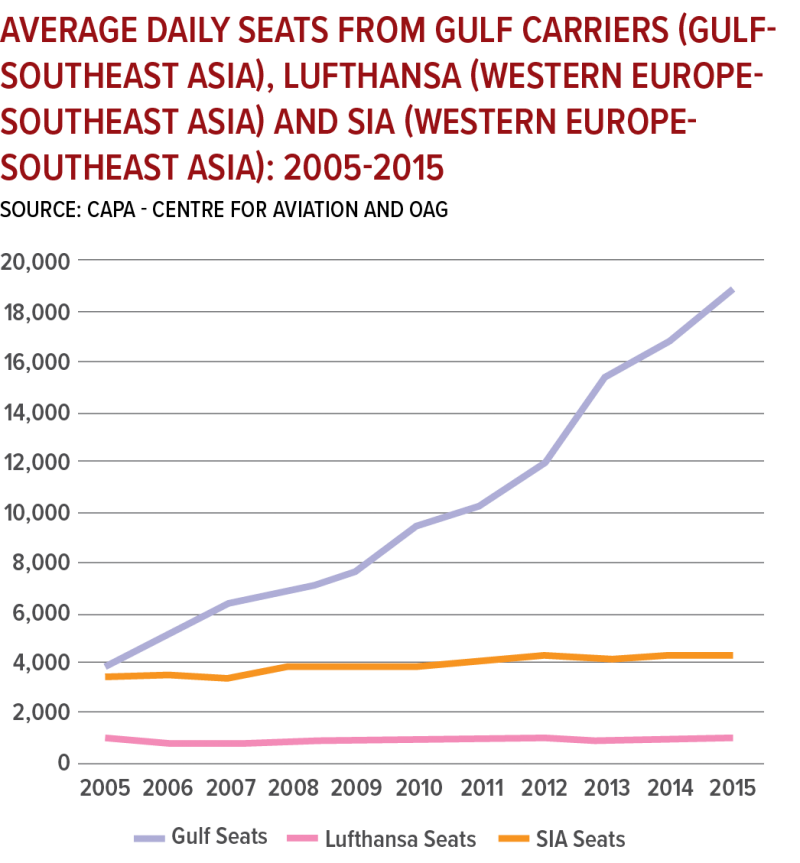

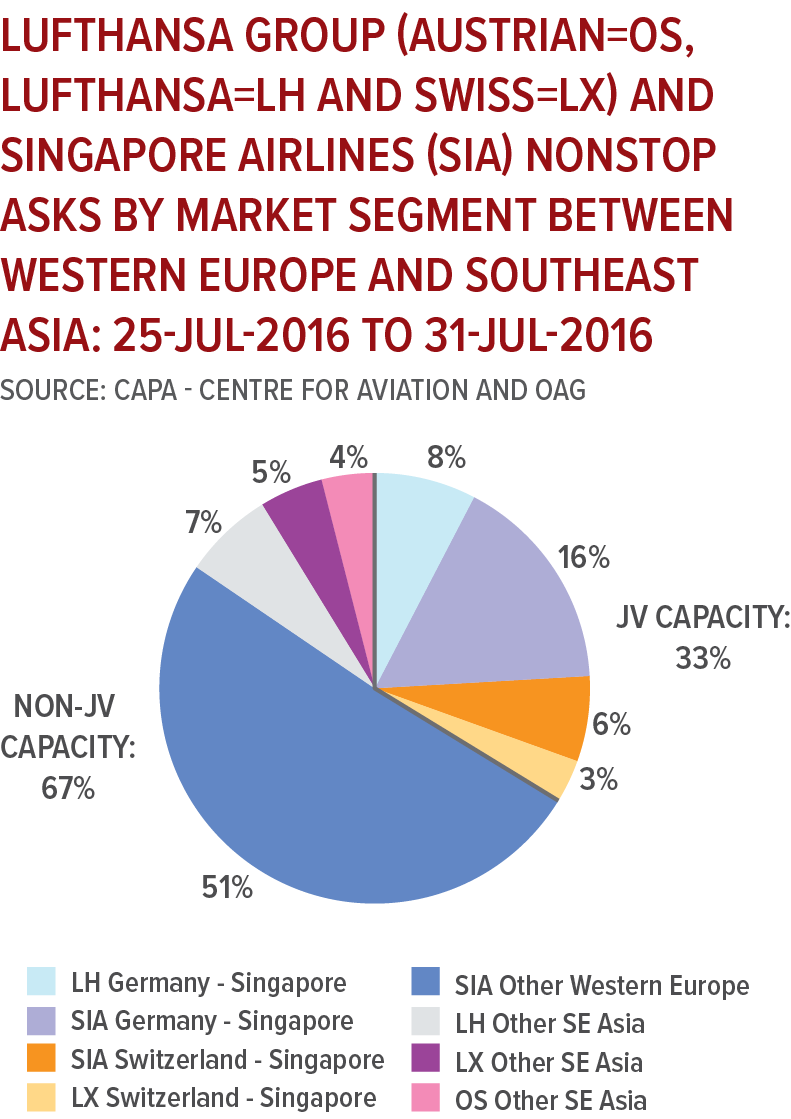

The challenge in Southeast Asia will remain the Gulf airlines. Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines together account for about 27% of non-stop Southeast Asia-Western Europe seat capacity. But when also counting passengers flown through all connecting points their share of the market is only 13%, according to OAG Traffic Analyser data for 2015.

Emirates alone has 12% of the market, and once Etihad and Qatar Airways are added, 27% of passengers between Southeast Asia and Western Europe now transit with the three Gulf carriers.

The Gulf airline influence is still growing. Oman Air is for example sprouting as a new, albeit smaller, airline. A second London Heathrow service and new Manchester flight reflect opportunities in the outbound European market. Kuwait Airways, although not close to even Etihad in size, is planning growth and will need higher connecting traffic to sustain limited O&Ds. Emirates has placed its 615 seat two-class A380 behemoth on service to Bangkok and, airports permitting, would like it elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

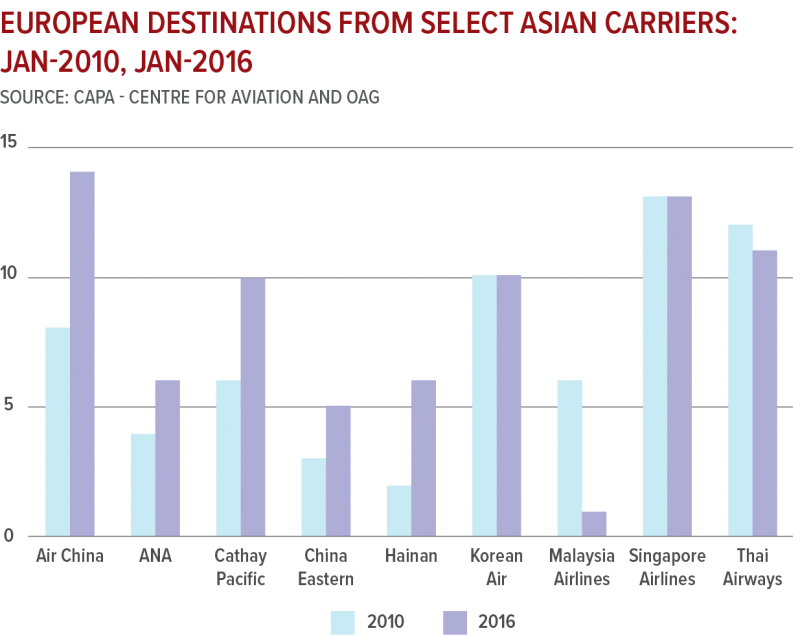

The largest southeast Asian airline flying into Europe is Singapore Airlines, which is second overall behind Lufthansa. SIA's strategy, seen at other Asian airlines too, is to focus connections on smaller Asian points Gulf airlines do not serve. That strategy is starting to come

under fire as Qatar for example launches service to thinner markets like Krabi. Gulf airlines have also used Bangkok Airways' excellent regional network to access smaller markets while other partnerships have formed: Emirates with Jetstar Asia in Singapore and more recently Malaysia Airlines.

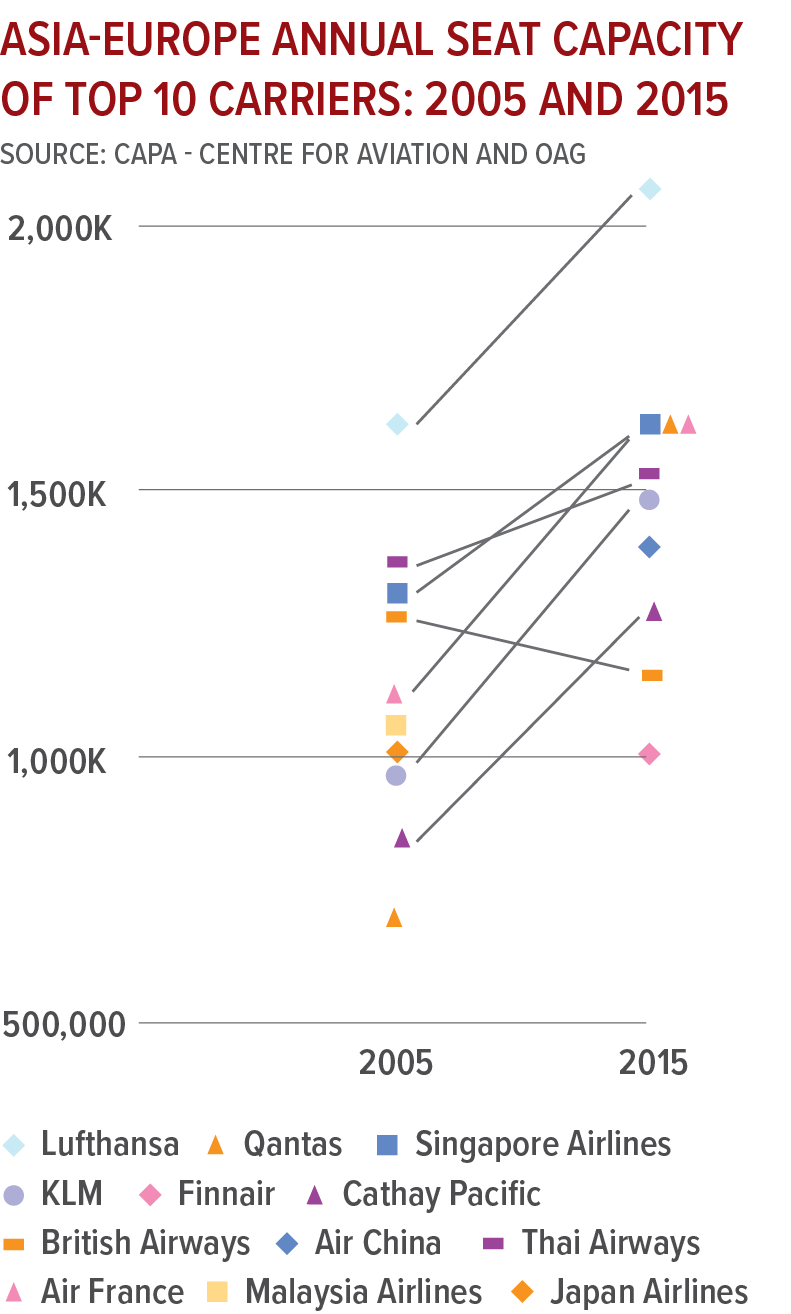

Despite the Gulf airlines making inroads in the Europe-Asia market, it took until 2015 for Singapore Airlines and Lufthansa to announce a JV. Seemingly mutual distrust diverted their attention from the real threat. The immediate focus is not growth but preserving market share and, possibly, yields. The slow build-up of the relationship - in time and market coverage - reflect the deep conservatism at Singapore Airlines.

In contrast, Malaysia Airlines bit the bullet. It has exited its European routes except for London Heathrow, itself even marginal. A number of destinations were cut before its partnership announcement with Emirates.

Thai Airways was once number two in the market, larger than even Singapore Airlines. It has fallen behind not only SIA, but Air France and Turkish Airlines have overtaken it too. Thai has lost much ground, and even a new pragmatic management team may be unable to reverse years of market share decline. But Thai, unlike SIA, has greater independence and it should not be ruled out that Thai too forms a partnership with a Gulf airline. A Gulf partnership with SIA is probably too radical for staunchly independent SIA.

Southeast Asia's smaller flag airlines - Vietnam Airlines, Philippine Airlines, Garuda - are each now planning growth but without a strong, or necessarily profitable, strategy.

While the Europe-Asia market is also about airlines from a third region - the Gulf - a fourth region is also relevant: Australia. Australia, with New Zealand, is typically the largest offline market for a European airline. Its market size may be more significant than some online Asian markets. This traffic has historically flowed over Southeast Asia but has shifted to the Gulf and is now poised to shift again over coming years - to mainland China.

With mainland Chinese airlines theoretically having larger O&D demand on Europe-China and China-Australia flights, they are in a strong position to discount connecting traffic. For the time being they lack scale, a solid transfer experience and premium traffic, but this will change remarkably by 2025. China Southern has coined the "Canton Route" for its aspiration to have a play at the Australia-Europe market by having it transit in its home of Guangzhou. Although well marketed, with the public surprisingly catching on, the traffic is still understandably small, given the large capacity levels flowing over the Gulf and Southeast Asia. Shanghai and Beijing can make a play too, and their O&D traffic will be stronger than China Southern's. Korean Air and peers never aggressively pursued the Australian market, let alone connections to Europe.

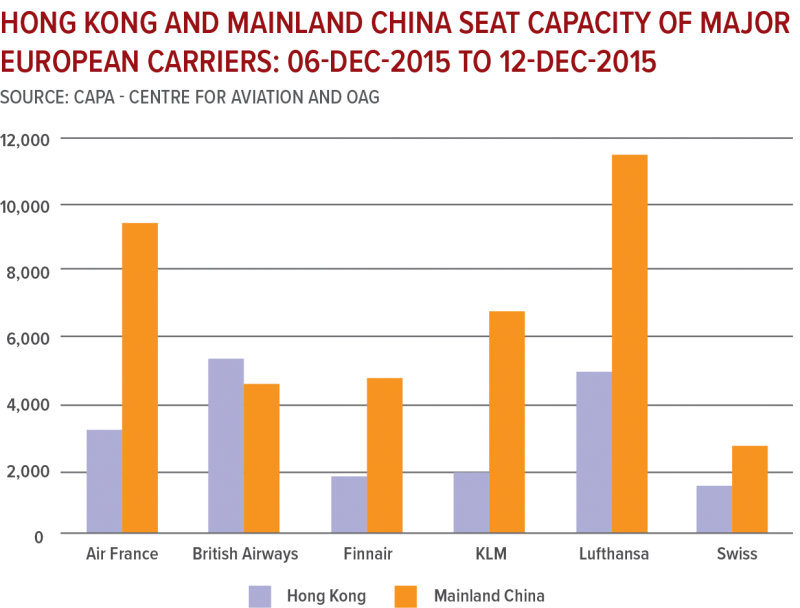

European airlines were initially the leader in opening secondary Chinese cities, made possible by subsidies. This market has plateaued with exceptions from Finnair, which is basing its future on long haul flights to Asia. Given its geographic advantage for Northeast Asia, and the dominance of Gulf airlines in Southeast Asia, it is Northeast Asia that is most appealing for Finnair and is where growth will primarily be. China is the largest opportunity for Finnair, as is typically the case in Northeast Asia.

Links from secondary Chinese cities to Europe are now mainly being added by Chinese airlines while secondary cities are also now adding long haul flights to Australia and North America. If allowed by Chinese regulators - and there is cause for optimism - Gulf airlines will have an increasing role in secondary Chinese markets. Chinese airlines each have only a handful of cities with non-stop service to Europe. Gulf airlines can access far more Chinese cities, although Chinese airlines, and their European partners, will benefit from each other's behind gateway networks.

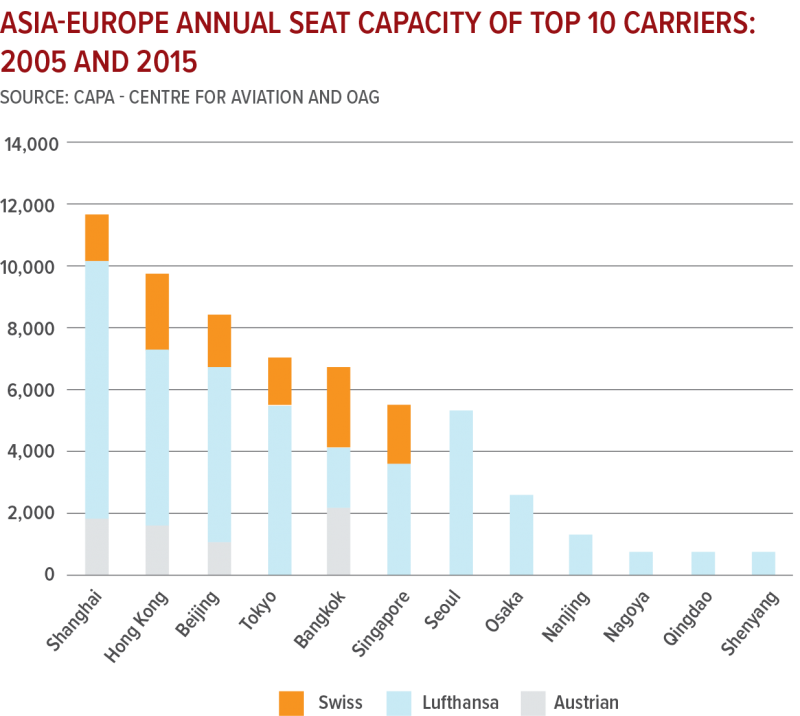

The role of hubs has been especially important for the growth of Europe-Asia routes. Air China serves Frankfurt, the hub of fellow Star member Lufthansa, from four Chinese cities. Brussels Airlines' ascension to Star in 2009 saw Asian airlines (such as ANA) over the years add flights to the hub.

China will re-shape, in a small way, the function of hubs and partnerships, as new major cities join the international aviation system. China's hubs today are mostly along the eastern coast. Officially, Chengdu (population, depending on administrative boundaries, 7-15 million) has been elevated to a hub, joining Beijing, Guangzhou and Shanghai. Chongqing, in close proximity to Chengdu in western China, is not far behind Chengdu in size and air links. Other western China hubs like Kunming, and to a lesser extent Urumqi, are eyeing growth.

The closer proximity to Europe of these new hubs means re-shaping the concept of long haul flights feeding short haul flights. Instead, these points allow two medium haul flights. At the extreme, at Sichuan Airlines' Chengdu base, Frankfurt is closer than Sydney. Even London, which Sichuan Airlines does not serve, is closer to Chengdu than it is to Sydney. Although Air China has a grip on Chengdu, the Chinese airlines are still contesting the right to develop a western hub.

New aircraft technology could allow for a far western Chinese hub to reach thinner European cities. Beyond China transfer traffic need only be small: routing over Chengdu to another Chinese city is potentially shorter in distance than via Beijing or Shanghai. A smaller hub will also theoretically provide a faster transfer process and have less need to operate in congested airspace.

Partnerships would need to take into account the Europe-China flight not counting for as much of the total trip revenue. Expanding the scope of JVs to behind gateway markets, a complicated calculation, could become more necessary.

Hub changes are having impacts elsewhere. The expanded network of international flights, and in particular daytime services, at Tokyo Haneda Airport is allowing some traffic to flow back over Haneda from Seoul Incheon. When, a few years ago, Japan's international flights mostly departed from Tokyo Narita, international demand from other Japanese cities would use Seoul Incheon. Incheon had the advantage of same-airport connections from a regional Japanese point onto a long haul flight, whereas transferring in Tokyo meant switching from domestic Haneda to international Narita. A Haneda domestic-international connection still requires a terminal transfer across a runway, but it is now a stronger proposition.

Japanese airlines have focussed on end-to-end partnerships in Europe, in contrast to the way they have carved a role as a transfer point for North America-Asia traffic. ANA, as is the case in general, has been growing internationally while JAL is not adding capacity, partially held back by restrictions imposed during its bankruptcy re-structuring, and partially because JAL's organic growth is very conservative.

The Korean airlines are growing carefully. They are deeply worried about Gulf airline inroads and hence fiercely lobby against allowing them additional traffic rights.

Japanese airlines instead have cemented partnerships, ANA especially, since it has historically (but no longer) been the underdog that needed to be creative to advance. Its relatively rapid growth would not have been possible without the Lufthansa Group in Europe, with whom it has a JV. The JAL-British Airways JV, extended to Finnair and soon Iberia, is not as important given that partnership's smaller size and stronger focus on O&D instead of connecting traffic.

Star Alliance's Asiana has an ambivalent relationship with many and is a deeply localised airline in its passenger target and ability to do business with others, allowing SkyTeam's Korean Air awkwardly to have a partnership with Star's Lufthansa. European airline interest in Korea is different from Japan: Korea's geography is compact enough that there is limited need for access behind Seoul. There is Busan, but even that city, like others in Korea, is better accessed by high speed rail to Seoul.

Europe-Asia JVs are proliferating but remain a patchwork: Lufthansa is most active, with three JVs covering Asia: with ANA, Air

China and one with Singapore Airlines. As Air China reshapes to offer sixth freedom traffic in coming years, it will target Japan and even Southeast Asia. Air China will also play its hand with connections to Australia and New Zealand, but not as prominently as China Southern is already doing.

There are very loose and limited partnerships between both China Eastern and China Southern and members of the AF-KLM Group. For its European debut, Xiamen Airlines is relying on a JV with fellow SkyTeam member KLM; both serve Xiamen-Amsterdam. Smaller Chinese airlines are less fortunate as they do not have an immediate European airline to call on. They consequently tend to focus on low yield but relatively stable tour agency sales that, over time, can migrate to FIT.

The JV patchwork could grow more colourful. Air France-KLM need a stronger solution, especially for Southeast Asia and offline access to Australia. A JV with Etihad has been discussed for a few years but Air France has a well known antipathy for the Gulf airlines.

Air France and Singapore Airlines were reported to be considering a deep partnership, even JV, in the France-Singapore market. This could create some difficulties, given the new JV with Lufthansa. The fact that there is any discussion at all is due to France being a strong enough market for SIA that it does not want to leave access via Lufthansa hub connections.

Oneworld's British Airways would like to form a JV with SkyTeam's China Eastern, which senses an opportunity to be at the core of a partnership rather than fight for attention in a SkyTeam-dominated China-Europe market.

Chinese partnerships have the potential to reshape global aviation. BA's advances also highlight how airlines are shifting from Hong Kong to mainland China as the preferred, larger destination, and market for partnerships. This could also reflect a feeling that there are better deals to be done than with Hong Kong's Cathay.

LCCs will grow faster in the Europe-Asia market than the market average but from a very low base. Their opportunities will be relatively niche. Until the arrival of the new generation of smaller widebodies it was generally considered that the long haul LCC sweet spot is around eight or nine hours, after which point fuel takes up such a large portion of operating costs that the portion LCCs can differentiate on is limited.

New generation airlines like Gulf carriers are almost effectively long haul LCCs given their greater efficiencies and lower cost structures, which European airlines - even LCCs - struggle to compete with.

European long haul LCCs, Norwegian and Eurowings, have so far focused on Thailand, a predominantly leisure market. To some extent they are replacing historical charter airline capacity following the shrinkage of the charter model in Europe and the UK especially. Gulf

airlines will have advantages providing one-stop service from a number of UK cities to smaller Southeast Asian points, like Krabi, that LCCs would struggle to compete on with partnerships at both ends. AirAsia X has talked of resuming service to Europe, and may be further encouraged as SIA's Scoot plans to commence in 2017.

Scoot's foray into Europe is largely at the behest of owner Singapore Airlines. SIA is looking to transfer some routes to Scoot, having decided the thinner 777-200ER markets are better suited to Scoot's 787-8s than Singapore Airlines' larger A350s or even 777-300ERs. Feed from Scoot's network and that of Tigerair, Singapore Airlines and Silk Air will be critical.

Although tempting to portray this as a model for future replication, Singapore Airlines' cost base is relatively high. Airlines with more competitive cost bases would not necessarily see cost advantages in a long haul LCC. Singapore Airlines' premium product is very generous and the airline is reluctant to discount, leading to empty seats; other airlines' premium products are more of a compromise and are more frequently discounted. Front-end revenue significantly changes the equation of flight profitability and if those seats are not filled, it is hard to maintain a yield premium to justify the higher costs.

Over the next decade and despite some development on the LCC front, new market entrants will continue to be from the Asian end, and in particular mainland China. Some additional European airlines will also enter or increase service. Iberia in 2016 returned to Asia, and Aer Lingus, also part of the IAG Group, is also likely to do so. Market share gains will be made by Turkish Airlines, Finnair and Aeroflot as they leverage their hubs. LOT is also emerging as a smaller player in this category.

Aeropolitical limits affect Northeast and Southeast Asia differently. Southeast Asia is relatively liberal, the main constraints being accessing slots at congested European airports for those airlines looking to grow. European airports are eager to secure connectivity from new airlines.

The proposed EU-ASEAN open skies agreement would potentially change the shape of the market, although the withdrawal of the liberal voice of the UK from among the EU negotiators will cast a cloud over those talks.

Such an agreement would create a standard access regime across each region and for example allow an EU airline to fly to ASEAN from any EU airport other than one in its home country, and an ASEAN airline to fly to the EU from an ASEAN airport other than one in its home country. So Lufthansa could fly London-Bangkok while Singapore Airlines flies Jakarta-Amsterdam.

Yet the history of EU-US open skies shows such routes are unlikely to eventuate; EU and ASEAN airlines rely on their hubs and would find it difficult to sustain a service without their local hub. Pragmatically, slot constraints at key airports would make it difficult to launch a service. It would be more attractive to use a slot on a local rather than long haul flight not touching a hub.

Long haul LCCs, with their propensity to operate from outside their home base, may benefit from additional access, but their growth as noted will be relatively limited. Norwegian International could operate on the strength of its London Gatwick hub, but Norwegian also has a Norwegian UK license. Early indications are that one third of Eurowings' traffic connects onto the long haul flights. There could be some value of open skies in allowing Eurowings to operate from one of its hubs outside of Germany, such as Vienna.

The traffic rights situation is more complex in north Asia. In some markets, European airlines account for all or most of the market from their country to China, such as Finnair and SAS. But in markets like Germany, which has bilateral rights, its airlines are unable to use them in full as they cannot secure Russia overflight rights. This is not a Chinese restriction but one which hampers German airlines' expansion. Extending the EU open skies mandate from Qatar/UAE/Turkey to China appears to be a leap for both the EU and China.

Wherever traffic from China is involved, reduction of visa restrictions has an important impact on market growth; US traffic spiked once the two sides concluded a 10 year visa exchange. Schengen visas are going in the opposite direction as new requirements make it more time consuming and logistically challenging to acquire a visa. It is yet to be seen if this implementation period is smoothed out or presents a medium term challenge until there is near liberalisation of visas.

The UK market has been disadvantaged with Chinese visitors as its visa only grants access to the UK; a Schengen visa grants access to the entire bloc. A Chinese tourist on a Schengen visa can take in multiple countries, a popular way of visiting Europe. The UK is looking to piggyback by pairing its visa with a Belgium-issued Schengen visa. The Brexit referendum and resulting decline of the British pound may increase the UK's appeal to Chinese visitors. However, this and other inbound growth is unlikely to offset the large decrease in UK outbound.

Europe-Asia is arguably the global long haul market that features the strongest competitive elements. At present North America-Asia and North America-South America may be characterised as wins for the consumer with overcapacity, but fundamentally the structure of Europe-Asia is the most difficult for airlines. There are strong, established competitors on either side with hubs throughout the region and strong intermediaries.

The trans-Atlantic is controlled between three JV entities while the trans-Pacific largely relies on Northeast Asian hubs with no intermediary options or large-scale fifth freedom services.

The opportunities for such orderly development in Asia-Europe are less obvious. The large number of markets at each end of the market and the great variety of airlines and legal systems will make similar coherence difficult to achieve.

Few markets can be protected from competition. Japan appears safe but there is a capacity exodus and over the next few years, Japan's airlines must either reduce costs dramatically or allow more cost effective airlines to supplant them. Korea is keeping the Gulf airlines at bay but has already unleashed opened access to Chinese airlines, a larger threat in the long term.

Southeast Asian airlines meanwhile have arguably missed opportunities to adjust to the new reality of competition by seeking new partners and business solutions. They are experimenting actively, for example, by establishing groups and cross border JVs.

Overall, Europe-Asia appears likely to be a truly innovative and world changing market. China's ascendance inevitably will generate massive change, both in terms of new entry and routes, but also in influencing the nature of the bilateral system. And, from north to south, it is already apparent that this fast growing region is capable of great innovation and of absorbing high levels of competition.