The Middle East long haul markets

The future will involve partnerships, and some new large hub carriers. Looking back in 2025, the Middle East might appear little changed from 2016: the world will be aghast, and some displeased, that three Gulf airlines and a fourth (not strictly from the Arabian peninsula but with favourable geography and a domestic market) have defied the odds to become global airlines with high growth, and more to come.

Yet these airlines may not be Emirates, Etihad, Qatar and Turkish but instead Kuwait Airways, Oman Air, Saudia and Iran Air. Each shares the favourable geography of the Gulf carriers, but as is often the case in Middle East aviation, everybody under-estimated the other. One other uncontrollable ingredient they will need though to achieve that position is a liberal market environment, apparently something that can no longer be taken for granted.

The success evident in 2016 of Gulf network airlines is inspiring others to imitate the strategy, and claim back some of the traffic their peers have funnelled to support their hubs. At play in 2016 are ambitions from smaller airlines to grow exponentially and take a role in transfer traffic. This includes Kuwait Airways, Oman Air and Saudia. Extending the geographic borders of this populous and well positioned region, Iran Air and Pakistan International Airlines are also eyeing not just a revival but surpassing previous achievements.

Egypt Air, Middle East Airlines (MEA), Jazeera and Gulf Air are not so motivated. Egypt Air's future is tied to local stability and final removal of government interference. MEA and Gulf Air have smaller local markets while Syrian Air, Yemenia and airlines in Afghanistan and Iraq remain small players.

Physical positioning is not a guarantor of success. Geography is only one ingredient and mastering all the components is a hurdle even for established airlines like Lufthansa and Singapore Airlines. For the

up-and-coming Middle East airlines, the challenges are immense.

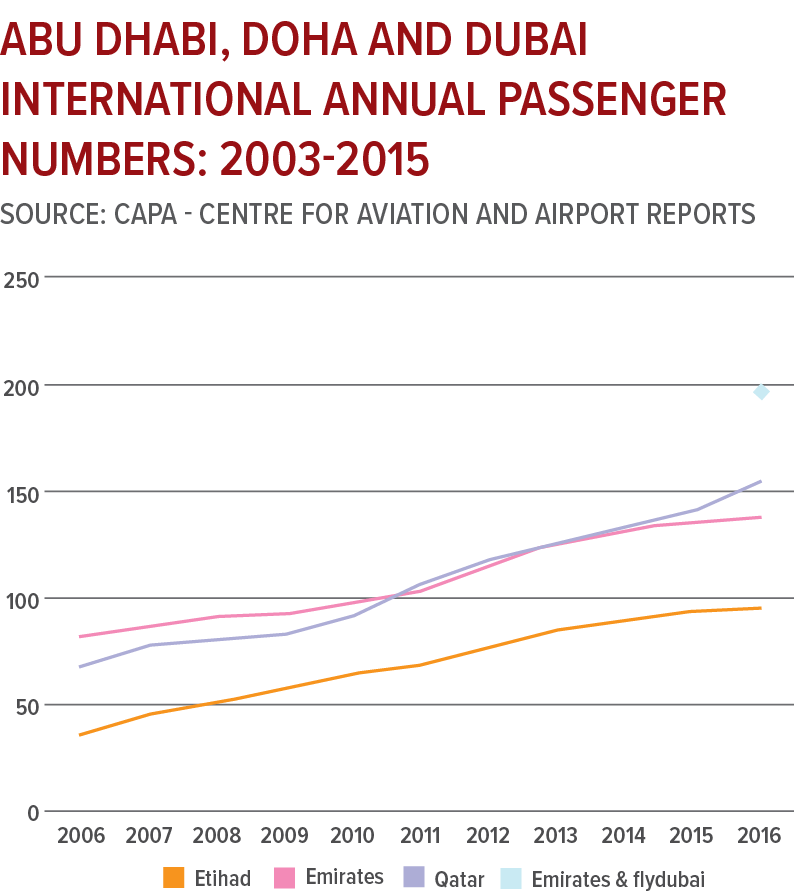

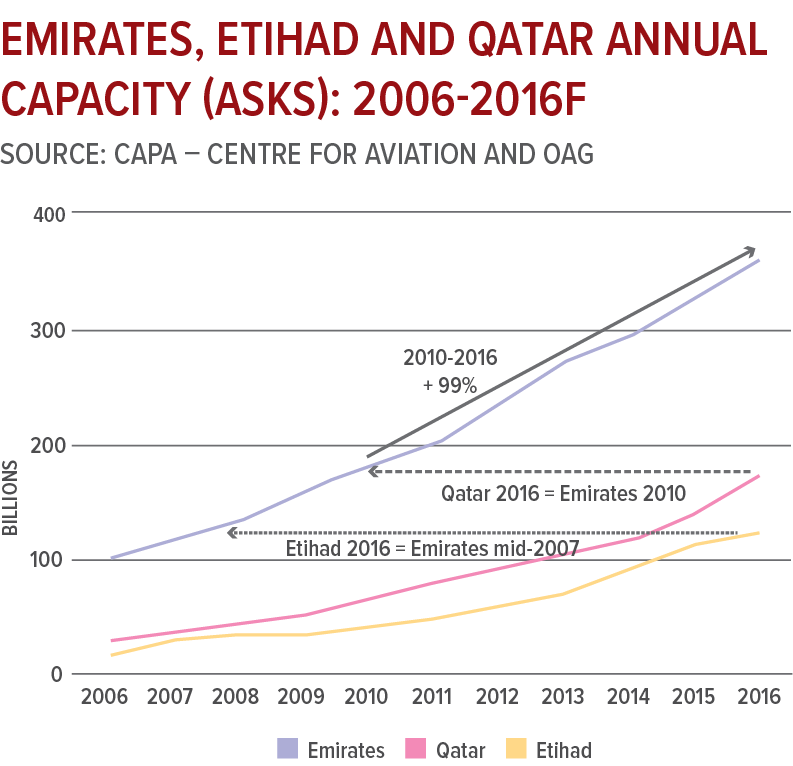

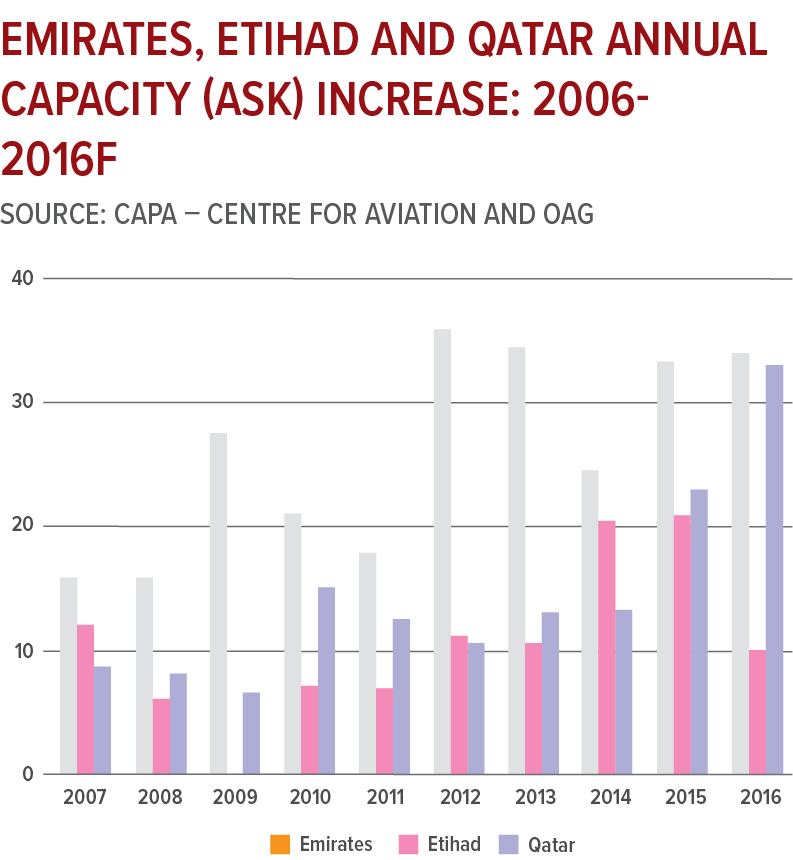

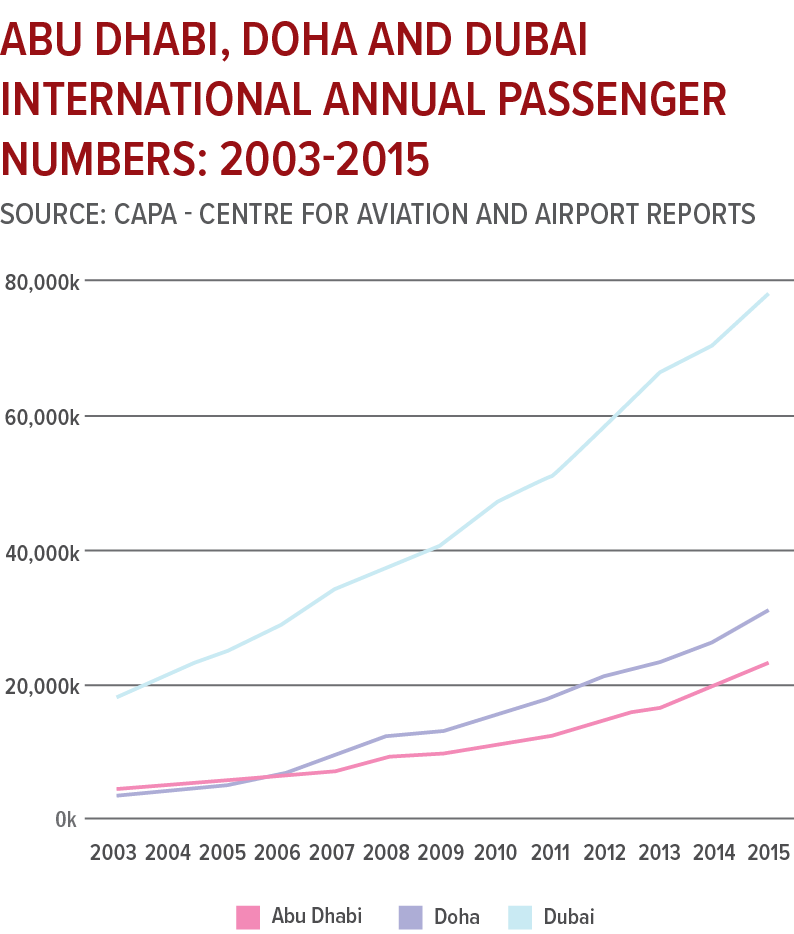

There is no prospect this new crop of airlines will surpass Emirates, Etihad, Qatar and Turkish. Within the Gulf three, Emirates will surely remain the largest followed by Qatar, but Qatar is rapidly growing to narrow the gap with Emirates. As for other contenders, Iran Air has the greatest potential given the size of its local market, geography and national willingness to return to the days when Tehran was a hub. It gives the Gulf three cause for concern.

Oman Air recently reportedly spent a record USD75 million for a single Heathrow slot pair, apparently a record although only a minority of transactions are public and Oman Air's slot is at prized, and most valuable, hours: it will have the earliest arrival into Heathrow of the Gulf airlines. The slot is Oman Air's second Heathrow service, and Manchester will also be launched as Oman Air builds up hub traffic. Yet all of this is from a country with a population under 4 million; the UAE is under 10 million.

Despite these startling growth spurts, Oman Air cautions it will never reach the size of an Etihad. Etihad, in turn, says it will not ever be the size of Emirates. Yet change in the Middle East happens quickly; Emirates is twice the size it was in 2010, when it was already large. It might be asked if Oman Air will not match the size of Etihad at the same time or might in 2025 be the size Etihad was in 2010. Oman Air in 2016 has 14 widebodies; Etihad had approximately 30 in 2010.

Since late 2016 Iran has received attention for its potential hub capability; Tehran's geography and the country's large population and diaspora give it a head start. Another lurking sleeper may be Saudia. Saudi Arabia has disadvantages for the flag carrier: split hubs across two or even three cities and government interference (similar on both accounts to PIA as it seeks to win back local traffic).

Saudia is working to overcome this. Now that oil revenue is under pressure, the government is reviewing the hub strategy and looking to boost tourism. Yet aside from religious trips, local attractions are few and a tourism embrace will necessitate a whole of country change. Dubai may also have been built in the desert, but it took more than a generation.

Iran is more of a ready-made market and, unlike Saudi, has an efficient local workforce. Iran also has a sizeable and experienced, educated workforce abroad that could return. Existing capacity is small, so that significant change could happen quickly.

Market access is perhaps a greater unknown. Here Dubai was advantaged from early in its life, signing favourable or liberalised air service agreements. Many were signed when the benefit at the time was to foreign airlines. Over the years, the benefit (if looking only at national airline interest and not holistically) has firmly shifted to Dubai. But that outcome was only possible because, from the start, Dubai (and Emirates' owners) insisted on totally open skies.

The Dubai-Singapore bilateral allowed Singapore Airlines to hub from Dubai to other Middle East destinations. These services have now been withdrawn but Emirates, besides its multiple daily flights to Singapore, offers continuing service from Singapore to Australia. In hindsight, would Singapore - and other countries - have granted so much access if they had known it would hurt their national airline? (Importantly, the answer might even be yes; Singapore measures its aviation success not so much through the fortunes of its flag carrier, but for its airport and tourist arrivals.)

Turkish Airlines may already be an example. In 2015, it carried more transfer passengers than Etihad carried total passengers. Its ASK production in 2016 is forecast to be approximately the same as Emirates was in 2011. Turkish faces restrictive bilaterals to the east; Hong Kong for example will not grant a seventh weekly service, leaving Turkish with an unusual six times weekly operation.

Future growth will hinge on liberalisation. Some markets are open skies or heavily liberalised. But to exploit transfer markets effectively, each of the spokes must offer open access, something that not all countries are prepared to offer, being more intent on protecting their own airlines. Improvements are being made with China while there is cautious optimism that the new Canadian government in the long term will bring a more consumer-friendly approach to capacity allocation. Korea, with its global airlines, is a holdout but there should be improved access by 2020. Africa has been surprisingly, but not thoroughly, liberal with Gulf airlines and by 2025 their impact on linking Africa with the new world will have been felt for many years - probably generating regional economic growth that no home grown policy would hope to achieve.

An EU mandate has been established to negotiate open skies with some GCC countries including Qatar and the UAE. This may not produce liberalisation but over the long term economic sense should prevail with more access granted to the airlines.

Airport and airways capacity is also a constraint. For a region known for being a world leader, the lag in infrastructure construction has been surprising. The growth of today's smaller airlines, assuming they have government backing for expansion, will be driven by aeropolitical access and hub capacity. Despite being late on the scene, constrained infrastructure elsewhere could be to their advantage.

It is against this background of change, global pressure and a possible structural decline in premium traffic that market leader Emirates is looking to re-invigorate itself. This is worrisome news to airlines already deathly worried and unable ever to match Emirates' efficiency. Emirates is already a highly efficient airline by most metrics - to the extent its model can be compared with others. There is room for improvement in the usual areas but also the opportunity to make advances in new areas that will be difficult for others to replicate. In the long term these areas probably hold greater potential than cost efficiency improvements.

An important and unique issue for Emirates is the future of the A380. No other airline comes close to depending on the A380 as Emirates does. Peers Etihad and Qatar have token A380 fleets and Iran Air's A380 order may not eventuate at all. Emirates CEO Sir Tim Clark in Jun-2016 displayed an uncharacteristic pessimism about the future of the A380. There are still a few years for this aircraft programme to play out, but uncertainty could lead Emirates and Boeing to develop an even larger version of the 777X.

Where the Middle East leads in aircraft orders, partnerships are a small part of their profile. This varies in the region. Etihad has seen partners generate a fifth to quarter of revenue (profit not stated) but this will slow as Etihad looks to accelerate its growth faster than that of partner airlines. Qatar Airways is the only one of the three Gulf network airlines to have joined an alliance, but an early foray for oneworld peer Cathay Pacific saw the JV dissolved.

An IAG JV with Qatar is supposedly forthcoming and could indicate future potential for JVs with Gulf airlines. IAG and Qatar Airways would bring multiple hubs and routes together. In comparison, Qantas-Emirates was relatively straightforward as Qantas has only two daily flights to Dubai (both continuing to London) and this market for Qantas is more strategic systemwide than it is profitable. For IAG and others who need to follow, there is much at stake.

Watershed partnerships remain a possibility. The German government is pressing Lufthansa for a solution to its woes. "Walling off the market won't help, and the Gulf carriers have a geo-strategic advantage due to their location," Brigitte Zypries, the Economy Ministry State secretary who coordinates Germany's aviation and aerospace policy, told Bloomberg in Jun-2016. "One should think about other possibilities… The English have demonstrated how such cooperation could shape up, and it makes sense to consider that."

Yet for a potential Gulf partner, the clock and scale may have ticked over. Whereas a few years ago a Gulf airline may have signed up for a

Lufthansa partnership, the Gulf airlines have had to stand on their own, becoming so large and strong that Lufthansa may no longer be seen as a useful partner - other than perhaps to neutralise its opposition.

The Air France-KLM Group has for a few years been exploring a deeper partnership with Etihad but nothing has eventuated; Air France has enough difficulty with its unions even making small adjustments. Singapore Airlines is unlikely to dance with the devil but Thai Airways, becoming more commercial, agile and free of government influence, could form a Gulf partnership.

All three Gulf airlines would like a deep partnership with a US airline, and surely by 2025 at least one such partnership will have to emerge. American Airlines is the most obvious candidate, having partnerships with both Etihad and (oneworld's) Qatar, and actually growing them while complaining against the Gulf three to the US government in 2015. Aside from their (very significant) North Atlantic JV partners, there is particular synergy in working with the Gulf airlines, with little route overlap.

Qatar Airways is looking at partnerships, from Royal Air Maroc to Meridiana in Italy, often due to sovereign interests. Emirates is selectively expanding partnerships - TAAG and Malaysia Airlines - and could continue to do so. It has shown particular interest in African LCCs, which are increasingly linking the continent and do not have any long haul traffic that could be jeopardised by partnerships from airlines outside of Africa.

By 2025, Emirates will be at its new Dubai World Central hub and re-united with flydubai. Like Emirates, flydubai is owned by the Dubai government but Emirates and flydubai are managed separately and have little to do with each other. Timing will be good for the two. They will be back at the same airport, able to have the flexibility needed to make a partnership that benefits Dubai. Oman Air and Saudia will need to work with their countries' new national LCCs, Salam Air and flyadeal.

2025 will bring a larger population of foreigners, already inclined to use LCCs, and a greater willingness by locals to use LCCs. This bodes well for Air Arabia, flynas and any future additional LCCs. As has been the

case elsewhere, LCCs can be a catalyst for change at full service airlines even if there are valid structural differences between regions. One of the biggest challenges for LCCs is full service overcapacity in regional markets, where too often access restrictions remain. Market share battles should have ended by 2025 as airlines become smarter with capacity, perhaps by shifting production to lower cost platforms.

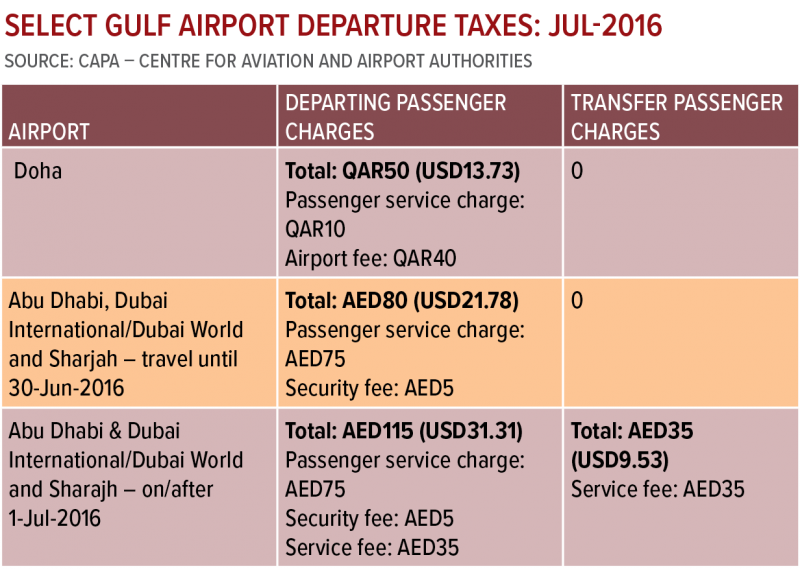

The more immediate future requires a solution to air traffic control congestion. Reported changes to be implemented in Dubai in late 2016 are encouraging steps for the needed sweeping changes that cannot wait until 2025 - or even 2020. Increased airport fees and introduction of transfer charges is not welcome but perhaps pragmatic from the point of view of governments in need of revenue and without unlimited airport capacity. The greater concern is that other airports, with less guaranteed sources of traffic, replicate what they see as a role model in Dubai.

Overall the internal challenges in the largest Gulf markets are comparatively few, but require action. There are greater challenges in other Gulf markets and the wider Middle East, and it is mostly from here there could be the largest changes in competitive landscape by 2025.

For all of them, a liberal access regime will delineate their success or otherwise. A rollback of liberalisation may be possible, but there are also signs of acceptance of new hubs.