Airports - subject as always to the vicarious uncertainty of airline fortunes

CAPA's 2016 outlook was against a background of unusually high levels of profitability for airlines.

In 2017 those profit levels may be eroded as oil prices creep back up, economies falter and political uncertainty abounds over matters such as 'Brexit' and the election of a new and unpredictable US president - along with the prospect of greater levels of protectionism and threats to open skies agreements. All of which, of course, must impact on airports.

Perhaps nothing sums up this political uncertainty more than the 'decision' made - at length - by the British government that London Heathrow Airport will be expanded by the addition of a single runway, and which is not a decision at all. It must be rubber stamped by MPs by Dec-2017 and there is no 'certainty' about that. On a potentially more positive note however, Donald Trump's election as US President could generate new, much need investment in US airport infrastructure.

The UK runway debacle has also focused attention on other airline matters of great import for airports. What, for example, is the future of the airline alliances on which global hubs like Heathrow and many others are predicated? If the CEO of IAG and the president of Emirates are to be believed those alliances have had their time and might not even exist 10 years from now as long haul low cost airlines continue to get their product right and grow in the way AirAsia X, Scoot and Norwegian are doing; all narrowing the gap to reaching profitability.

Taking Europe as an example, according to figures from ACI Europe, most of the growth at European airports over summer 2016 occurred at airports handling between five and 25 million passengers p/a. Small secondary level regional airports grew at a much slower pace, while traffic at Europe's five largest hub airports - some of which are severely capacity constrained - remained flat.

That is not necessarily the case in other regions. Secondary airport growth is still a feature in China and Korea, though less so in Japan and Taiwan. In Northeast Asia as a whole, airports where there are slots available are seeing strong growth, whatever their size, and in the Middle East the big hubs continue to dominate growth.

So the evolutionary picture is emerging of a voluntary change in at least one region in the distribution of air services by all airline types in favour of sub-primary airports in heavily built up areas - rather than global hubs in global cities or secondary level regional airports.

Just one of the many reasons for the shift is the propensity for LCCs increasingly to consolidate their services at primary airports where anticipated yield is typically higher, while avoiding global hubs. Ryanair is moving into Frankfurt International, though it is only a toe in the water so far. Some of them have done so via a process of hybridisation that involves taking on characteristics of full service carriers.

This shift in favour of sub-primary airports may reflect the growing propensity for corporate travel managers to avoid the inclusion of LCCs in their travel policies, as revealed at a recent CAPA event.

And it may at least go some way to explain the stalling of LCC capacity growth from a global perspective in 2015 and 2016.

Global passenger numbers are expected to rise by 4.9% on average until 2040 (ACI World) and by 3.7% until 2035 (IATA). Despite the discrepancy in those figures both organisations are in agreement that while growth is anticipated to remain solid in mature markets over the medium term (e.g. Europe, North America), most long term growth is expected to come from emerging economies with IATA singling out China, which will displace the US as the world's largest aviation market by 2029.

This also applies in India, Indonesia, Vietnam and perhaps surprisingly Africa, where the top 10 fastest growing country markets cut a swathe across the central and eastern areas of the continent in their own version of the European 'banana', the trans-national shape of economic growth in Europe.

2035 is relatively close in aviation terms and it is interesting to look at how these countries are already preparing for those growth levels. The data source is CAPA's Global Airport Construction Database (GACD). The GACD currently counts 2,472 airport construction projects at existing airports - confirmed or anticipated - in 81 countries, which is 100 less than at this time in 2015.

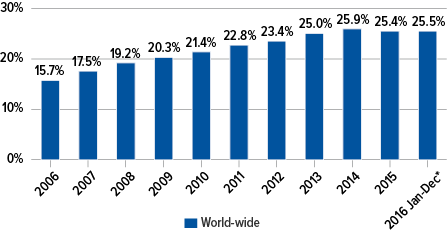

Additionally, 405 new airport projects are either confirmed, under construction or anticipated worldwide, which is an increase of 17 over 2016. Their distribution is outlined in the charts to the right, which are configured to display investment amounts in USD.

Additionally, 405 new airport projects are either confirmed, under construction or anticipated worldwide, which is an increase of 17 over 2016. Their distribution is outlined in the charts to the right, which are configured to display investment amounts in USD.

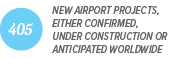

LCC capacity share (%) of total seats: 2006 to 2016 Jan-Dec*

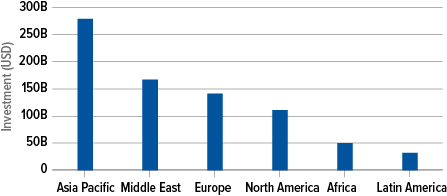

Airport projects by region, investment amounts (USD) as at Dec-2016

New airport projects by region, investment amounts (USD) as at Dec-2016

The dominance of Asia Pacific in these charts is evident although Europe leads the field in the number of existing airport projects; it is Asia Pacific that spends far more money on them.

Expenditure on both existing airport and new airport projects in North America (the US and Canada) remains low, and especially in the case of new airports. However, the increasing number of public-private-partnership deals in the US, perhaps fuelled under a Trump administration, and the prospect of privatisation in Canada (see investment section below) encourage the prospect at least of greater infrastructure construction activity there.

Overall, more is being spent on existing and new airports in Africa than in Latin America.

2017 will not see the completion of any of the biggest and most interesting projects in the airport sector, but they edge closer to it. Numbered amongst them are Istanbul Grand Airport (2018, first phase), which is a potential competitor to the MEB3 airports if the political situation in Turkey stabilises; the new Mexico City Airport (2020, first phase) where traffic projections could be adversely influenced by the US presidential election result; and Beijing Daxing (2019, first phase).

One airport project that might be completed in 2017, unless more reasons are found for it not to be, is Berlin Brandenburg International (BBI), which should have opened in 2011. The latest projected date is 1Q2018. Berlin's passenger traffic has been growing dramatically, by 44% in Sep-2016 and Oct-2016; this airport is long overdue.

Intriguingly, the private sector is again showing interest in investing in BBI, which began life in 2006 as a private sector initiative. The total number of organisations investing directly in airports (current, historic and projected) and listed in the CAPA Global Airport Investors Database (GAID) is currently 714 - 64 more than at this time in 2015.

Just as the airlines have enjoyed unprecedented profits in the last two years so has private sector interest in airports been revitalised, boosted by strong airport financial performance and even though it remains the case that the majority of the world's airports continue to be loss makers. It is at those global hubs and sub-primary airports that the money is being made.

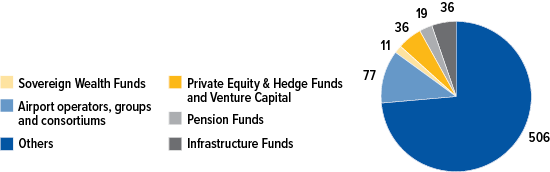

A growing number of international funds (over 100) are attracted to those airports and now constitute the largest investment class in the industry, competing head on with the banks. The chart below, from the CAPA report 'Global Airport Finance and Privatisation Review 2016 - the day has come for the PPP' published in Sep-2016 (with data from Jul-2016), shows the distribution of airport investing organisations by type.

Airport Investors 2016

The same report makes extensive reference, as its title suggests, to the growing number of public-private partnership (PPP) transactions. In the wake of the failure of the Airport Privatisation Programme in the US, which was intended to pave the way for airport leases to private sector operators, the PPP will be one of the few methods by which the private sector can partake in much needed infrastructure provision at US airports. The US FAA projects that USD32.5 billion will be required in airport construction and renovation projects in the US from 2017 to 2021.

The CAPA report counted 10 US PPP projects, the best known of which are New York LaGuardia Airport's USD4 billion central terminal construction (LaGuardia Gateway Partners) and the Ferrovial Airports-led main terminal reconstruction project at Denver International Airport. The PPP is the way forward now for the privatisation of US airports; it ticks most of boxes where governments are concerned.

Expect to see more PPP contracts involving smaller airports there, such as that negotiated between Westchester County Airport and Oaktree Capital Management, which takes the form of a 40-year revenue sharing lease with the airport receiving a USD111 million upfront payment.

The airport will continue to be owned by the county and will be privately managed by Oaktree. By structuring the lease in accordance with the terms of the FAA privatisation programme that allows small to mid-sized airports to be run as public-private partnerships, money paid to the county by Oaktree can be used for all county programmes, not just those at the airport. It is regarded as a PPP, not a sale, and circumvents many of the inhibitors to privatisation experienced in the past.

In Canada the issue is not of PPPs specifically but of whether privatisation should replace the not-for-profit stakeholder ownership scheme that is in practice now. A government report early in 2016 suggested it should. The Liberal government is determined to privatise major state-owned assets and enterprises and use the proceeds for investing in infrastructure. The matter is now with an investment bank for the review and assessment of airport privatisation options, and it was expected to report by the end of 2016. The problem for the government is that only one of the largest non profit airport authorities - Aeroports de Montreal - has shown support for the proposal.

In the Caribbean there is growing interest in the potential privatisation of airports in Cuba from several of the big hitters in airport financing and development in Europe, but a process may take some time to materialise.

In Asia, the privatisation drive is most apparent in countries such as Japan, where the first two of what could be many PPPs have been concluded. Also Vietnam, which is privatising its main airport corporation via an IPO, while in the Philippines concessions on smaller airports could lead to much bigger transactions at other airports. Indian PPP privatisations have stalled but may re-emerge.

In the Middle East and West Asia there is privatisation activity taking place in countries that hitherto would not have been considered western investor targets, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, but in both cases those investors will need to exercise caution. Saudi concessions are expected to come on stream in 2017, with ambitious objectives set for airport privatisation there as the low oil price continues to provide the catalyst for economic reform in the kingdom.

In Russia, the privatisation of Moscow Sheremetyevo Airport and its consolidation with Vnukovo Airport (and possibly with Domodedovo Airport in the future) is making progress. There are now numerous private sector entities taking control of Russia's secondary level airports - in some cases individual entrepreneurs - and there is equity redistribution taking place at others, such as St Petersburg Pulkovo.

In Latin America all eyes will be focused on the third tranche of concessions on Brazilian airports, which has progressed slowly on account of the turbulence there. The reformist interim government plans to privatise four more airports within the next year: Florianopolis, Fortaleza, Porto Alegre, and Salvador. This time around, the state airport authority, Infraero, will not retain a 49% ownership stake in the concessions and it will not take part in future concessions at all. Indeed, the state entity Infraero may be withdrawn from participation in airports that have already been privatised and in which it holds a share.

There will be no restrictions on foreign ownership but it will be a much harder sell than the first two concession rounds as the government is playing hardball. An experienced airport operator must make up at least 15% of the consortium bidding for an airport. Concession holders will pay an annual fixed fee and a percentage of gross airport revenue each year for the full term of the concession. The proceeds will be used to assist development of Brazil's smaller airports, which is what the privatisation of primary airports in large countries like Brazil should really be about.

Moreover, legislation is expected to be passed by which the government would be able to reclaim concessions previously awarded and redistribute them to other parties, should certain criteria be met.

There is still little privatisation activity in Africa, despite all the construction there, as many negative preconceptions about the continent remain. However, privatisation of Nigeria's airports has edged closer.

The four largest airports there, at Lagos (which is already partially privatised by way of a PPP on its Terminal 2), Port Harcourt, Kano and Abuja, will be subject to concession terms but there is little apparent international interest in them and very strong and determined local opposition. As such Nigeria is a microcosm of the wider continent.

It is notably in Europe where the influence of the private sector continues to grow, almost to the point where it could be considered to be booming. 40% of European airports (both EU and non-EU) had at least some private shareholders in 2016.

In France, the Lyon and Nice airport concessions have been settled, with French firms involved in both successful consortiums this time, and that suggests it will be French and European companies that predominate in future transactions there. One of those companies, Vinci Airports, counts, along with TAV Airports (Turkey), as being the most active in the world presently in terms of live concessions and bids.

In Greece, the second tranche, of 23 Greek regional airports is to be concessioned out, following the 14 taken on by Fraport Greece early in 2016. Along with the sale of the government's stake in Athens Airport, these transactions must take place as part of Greece's economic bailout deal but they are, ironically, influenced still by the parlous state of the Greek economy. And as a group they are unlikely to be as attractive as the first 14.

Spain's Aena is still benefiting financially from its partial sale and float but has to decide on the future of many of its smaller airports while considering the merits of a further flotation or trade sale. Meanwhile, flush with cash (net profit +48% in the first nine months of 2016) it is back out on the foreign acquisition trail.

The opposite is the case in Italy, where the country urgently seeks private investors for many of its airports, which could otherwise be closed down - although that outcome will hardly attract them.

Strangely there is little privatisation activity anticipated in the UK. It is running out of privatisation opportunities except for on-sales, and has recently witnessed its third (albeit partial on this occasion) reverse privatisation. However, as mentioned earlier, rumours of the sale of London Gatwick Airport and Edinburgh Airport persist as a direct result of the government 'decision' to expand Heathrow Airport.

| Country | Airport | Notes |

| Japan | Kansai |

T2 - the low-cost terminal will be expanded to more than double its current size, to better accommodate current and future growth. To be completed in FY2016. |

| Japan |

Will construct a dedicated LCC terminal, stating the recent increase in new routes being launched by LCCs called for a restart to the project, which was first considered in 2013 but was shelved. Expected to be constructed and commence operations in late Sep-2019. |

|

|

Clark International |

The LCC terminal is scheduled to be completed in 2019. |

|

| Oman |

The existing terminal will be converted for use by LCCs, once the new terminal building is operational. The new facility is due to go into operation in either late 2016 or early 2017. |

|

| Germany |

Brandenburg International (BBI) |

The still unopened BBI plans to construct a EUR200 million, 45,000sqm low cost terminal, with capacity for eight million passengers per annum. |

In Eastern Europe the greatest amount of transaction activity is scheduled to take place in the east of Europe, in Lithuania, Bulgaria and Serbia.

In summary, private sector involvement in airport development continues to be an imperative for its continuing development, whether through the vehicle of the PPP or by other means. The amount of money being ploughed into airport construction globally is at an all-time high. These levels of investment cannot be sustained by governments and municipal authorities alone, and the PPP segment especially holds out great promise to investors and construction companies in the future.

The refocusing of the low cost carrier - at least in Europe - alluded to earlier may be premature but it is the case that less airports are catering specifically to their needs by building 'low cost terminals.' Singapore's Changi Airport for example did away with its 'Budget Terminal' in favour of inclusivity at terminals four and five and Kuala Lumpur's KLIA2, though touted as a low cost facility (and heavily used by the LCC AirAsia), hardly justifies that categorisation.

There are a few exceptions to this broad bush rule and they may be found in the table.

Apart from these exceptions most of the construction of low cost terminals will come in India where the Ministry of Civil Aviation aims to revive low cost/no frills airports and plans to operate at least 50 such airports within the next three years. The Airports Authority of India has said that some of them may be built as pre-fabricated structures that can handle 30-50 passengers per hour.

Additionally, AirAsia Group CEO Tony Fernandes has indicated his company hopes to break ground on new low cost airports across ASEAN in 2017. Mr Fernandes thinks the carrier will be able to deliver a fully operating airport in less than one year once it secures the necessary permissions. However, while it is the case that many secondary level airports in the region are ripe for this sort of development, LCC management frequently makes public comments about managing or investing in airports and terminals while few actually do so alone; it is a big commitment.

The one area in which the impact of the LCC segment within airports will continue to be seen, irrespective of separate terminals, is that of passenger self-connectivity. It is estimated by OAG that as many as 40% of US passengers are now bypassing typical booking practices, such as through an airline, travel agency or OTA, and are beginning to self-connect when they travel. Outside of the US, airports in Asia and Europe are making arrangements to cater for this new breed of passenger, but at different speeds, with London Gatwick Airport being a leader, as part of its strategic policy that sees formal global airline hubbing as a diminishing activity.

Meanwhile building ambitious airport cities and attendant aerotropolises has regained popularity. There are now more than 50 airport-related areas in China alone implementing aerotropolis principles. New or proposed developments include those at and around Muscat Airport (Oman); Stockholm Arlanda and Gothenburg Landvetter airports in Sweden; Moscow Domodedovo Airport; Accra Kotoka Airport in Ghana (a PPP project is desired there) and the Riyadh and Jeddah airports in Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile in Australia there is a growing movement to include an airport city in the design for the new Western Sydney airport at Badgerys Creek to improve job prospects there. On a smaller scale, Canberra Airport has successfully developed an array of satellites.

The common feature among many of these proposals is that the airports have a great deal of spare land at their disposal.

Some airports have even sought to capitalise on political events such as Vienna International's owner Flughafen Wien, which launched a campaign in the UK to attract businesses to its airport city in the light of the EU Referendum result.

A recent CAPA report examined the business credentials of the top 10 airports that have established airport cities or aerotropolises.

Away from construction and investment developments, other significant trends include the increasing number of high speed rail (HSR) lines that will interface with airports. One example is 'HS2' in the UK, which is now being pushed through quickly by the revamped British government although it will not be completed until 2033. It will connect firstly Birmingham Airport and subsequently Manchester Airport with Europe's busiest rail corridor and the important cargo airport at East Midlands on a separate line. If it is also connected to Heathrow Airport and to Scotland, both of which eventualities are uncertain at this time, it could remove the need for much domestic air travel in the UK.

On a much smaller but equally important scale a high speed rail line is to be built over the lava fields of the Reykjanes peninsula in Iceland, to connect Keflavik Airport with Reykjavik city in 18 minutes at 250km/hour, thus alleviating a road journey that can take up to an hour on notoriously unpredictable roads. At the same time it will dispense with the need for a domestic airport in Reykjavik.

And China's HSR network was built mostly with little consideration of airport connectivity, but is increasingly being integrated.

While UK and Iceland projects are long term (Iceland's will commence construction in 2020) there are many others, worldwide, with much shorter completion timeframes and they are reported regularly in CAPA's Airport Business Daily and by text alerts.

The US Secretary of Homeland Security recently announced that 11 new foreign airports, located in nine countries, have been selected for possible US Immigration passenger pre-clearance; this comes at an interesting time. Not only because pre-clearance may or may not necessarily square with the immigration objectives of the incoming US President, but because obtaining such privileges can be a huge advantage to an airport.

As revealed in CAPA reports on this subject in 2015 and 2016, airports such as Dublin in Ireland and Abu Dhabi in the UAE have not only been able to gain economic advantage over their rivals (for example Belfast, UK, is to lose its only direct US flight while additional trans-Atlantic services are being added frequently at Dublin, 150km away), pre-clearance facilities can actually divert traffic away from intercontinental gateways in other countries as journeys made under sixth freedom principles together with immigration clearance in the country of origin can be much more convenient.

The 11 airports identified as possible pre-clearance locations include those in Colombia, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil (2), UK, Iceland, Italy (2), Japan and Saint Maarten (Dutch Caribbean). They are in addition to others already announced in the same countries and in Belgium, Dominican Republic, Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Turkey, but pre-clearance operations will not begin until 2019.

Pre-clearance, which is fundamentally based on security needs, leads on to the initiatives that have come from IATA's Simplifying the Business (StB) programme, some of which will become prominent in 2017. StB looks at the passenger experience from an end-to-end perspective across all processes, from shopping for travel, to the airport experience, to arriving at the destination, with a special focus on transformation.

Among the initiatives is Smart Security, a joint initiative with Airports Council International to make airport security checkpoints more efficient and less intrusive. It is making inroads in Europe and the first US airport - Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport - recently joined the programme. Also One Identity, a concept that would allow an air traveller to assert their identity just once, thus eliminating repetitive ID checks at security, border control and the gate.

In Oct-2016 CAPA published a report on Transportation Network Companies (TNCs - the best known is Uber), their modus operandi and how they are evolving globally - especially in their relations with the airport sector.

The speed at which the TNC business is evolving and disrupting mirrors the changes in travel modes more widely, including those mentioned earlier, such as independent direct airline reservations and self-connection through airports; also online home-space reservation for business and leisure rentals as characterised by Airbnb.

These new players in the travel business know that what applies in the air transportation sector applies equally to them, i.e. that there is a big reward for being the biggest in a market because the service with the most passengers and drivers tends to be more economically efficient. Therefore huge investments, multiple product variations, alliance-forming for cross border activities and M&A activity can all be expected to increase in intensity. It is difficult to imagine how airports can avoid being dragged in to this maelstrom and those that have not attempted to formulate a policy to respond to their presence need to do so urgently.

The TNCs are just one aspect of an airport's relations with the motor vehicle, all of which are connected to environmental policies. Nothing that was said in last year's Airline Leader report on the subject of airport environmentalism has changed but at the same time it must be recognised that car parking continues to be the strongest revenue growth stream at many airports, irrespective of the impact on emissions, which continue to be a serious issue at Heathrow Airport for example.

In the first nine months of 2016 car parking revenues grew more (8.7%) at Heathrow than any other non-aeronautical stream apart from airside specialist catering. While at Manchester Airport Group's four locations car parking revenue growth of 12.4% in FY2016 left retail and aeronautical revenues trailing in its wake, driven by additional capacity, enhanced pre-booking channels and improved Meet & Greet products.

So one of the policy decisions airports must make is whether to support TNC services (which are theoretically slightly more environment friendly but which do not make them much money yet), or the addition of more parking space, which assuredly would.

It is hard to dodge the indicators that the airport competition battleground during forthcoming years will be on the approach roads and car parks as much as in the terminals and on the runways.

One final suggestion to all airports would be: Provide adequately for the Chinese market. While outbound travel from China was subdued by the economic blip in 2016, the potential number of Chinese tourists is so huge that they will appear in every market; they are usually Middle Class with lots of disposable income, and if they like what they see they can come back and invest in the city-region.

Already such diverse airports as Birmingham (UK), Keflavik (Iceland) and Dubai have taken the trouble to ensure Chinese guests are well received. Birmingham, which is the closest airport to Stratford-upon-Avon, birthplace of William Shakespeare and revered by educated Chinese, installed Chinese terminal signage and arranged staff cultural awareness training, Mandarin speaking front of house staff, specific web-pages translated into Mandarin, and a dedicated VAT refund facility for passengers to use before returning home.

Chinese visitors to Iceland, almost all of them through Keflavik International Airport, were the fastest growing segment in 2015 in a country that has established very large traditional markets on both sides of the Atlantic, while Dubai International Airport's CEO described the Chinese market as "incredibly important".