China’s emergence as an international force is provoking new marketplace conditions

Northeast Asia continues to drive growth, large in size, complexity and with future implications inside and outside the region. China is a singular attraction and remains in its golden years of expansion, with opportunity mostly constrained by infrastructure.

If not for runway, terminal and air space congestion, China would already be much larger.

Northeast Asia is not just China, and the vast other territories in the region are substantial in their own right. Flag carriers are expanding in size and footprint while seeing their domestic/regional networks fall under greater pressure, often due to LCCs. LCCs are burgeoning in Korea, Japan and Hong Kong despite local governments and partners hardly giving full support. Pressure is on at full service airlines from mainland China but also themselves as they have greater overlap with each other.

GDP growth is typically tied to aviation growth, but this is less relevant for China (OECD 2017 GDP growth forecast: 6.43%). If there was to be no GDP growth but a marked expansion of slots, aviation would still grow. Visa liberalisation, increased consumption of long-held savings, and the government's outwards push are key drivers not contingent on the exact (and often debated) GDP figure. Further, growth percentage decreases belie increases in net volume. Japan (1.03% - highest since 2013), Taiwan (1.7%) and Hong Kong (1.8%) do not have strong GDP growth rates but air travel will continue to punch way above its weight. Korea has slightly stronger GDP growth (2.6%), but its lively domestic market faces constraints, in a familiar refrain, due to lack of slots.

The growth and challenges in Northeast Asian aviation are reflected in a supposed exchange between companies: A full service airline, the story goes, complained of a low cost competitor: "They only fly the profitable routes!" "Yes," the LCC responded, "that's the point."

Yet airline objectives in Northeast Asia are not so binary as to say profitable routes good, unprofitable routes bad. There is the classic network element: a loss-leading service that retains corporate customers and feeds long haul sectors. Such examples are growing as airlines, for example, expand non-stop Southeast Asia-North America flights, taking traffic that used to transit in a Northeast Asian hub.

Many Northeast Asian airlines focus on growth - mostly, but not exclusively, in China. Airlines are opening short and long haul services in hopes of securing the market once it matures and has a chance of profitability. Chinese airlines are further in a race as traffic rights tend to be monopolistic under the "one route, one airline" policy.

A large portion of what airlines are doing today around Northeast Asia is unprofitable aiming at one day being sustainable. For some, it is a long shot, especially by aviation's volatile standards. Exactly what is "the point" of flying is being re-evaluated as competitors sprout and shrink and governments ease or grow influence. Whatever "the point" of flying is, some companies are moving away from being an airline and transitioning to a more stable, counter-cyclical group defined by aviation or even more broadly as a transportation/tourism or general lifestyle conglomerate.

Northeast Asia's most dynamic market in 2016 was perhaps surprising: Taiwan. There was cautious industry optimism as Beijing permitted Taiwanese airlines to carry ex-mainland China transfer traffic, albeit from a handful of very small cities. A gradual opening of the market was always expected and this started the process for China Airlines and EVA Air to grow their business with mainland China transfer traffic in the long term. Their existing size is remarkable since they, unlike competitors, have not had access to Chinese transfer traffic.

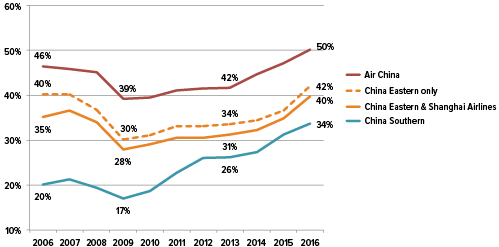

Proportion of scheduled ASKs in international markets: 2006-2016

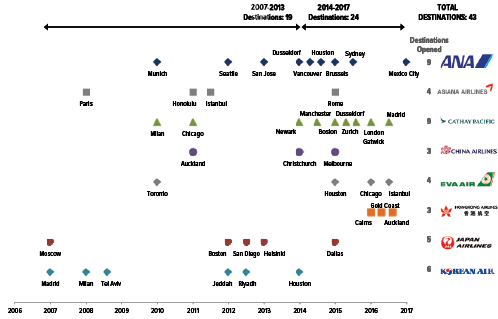

Northeast Asian airlines' new long haul destinations: 2007-2017

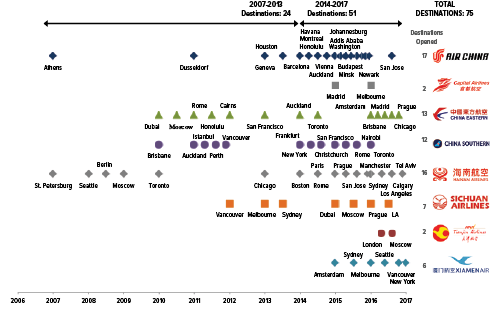

Mainland Chinese airlines' new long haul destinations: 2007-2017

Privately-owned EVA Air has been more aggressive than government-owned China Airlines. Once the owning family's patriarch passed away, an inheritance battle played out very publicly. This resulted in management change to a faction of the family that considered, as have some in the industry, that EVA's growth has been too ambitious.

As EVA considers dialling back growth, China Airlines may be shedding its sleepy image as Taiwan's new government wants to increase national activity. This government, however, is not welcomed by Beijing.

Aviation always has a political element; with China this is an important feature. Consequently there has been a rapid decline in the very profitable cross-Strait segment. The new Taiwanese government also replaced China Airlines' chairman with a new leader who immediately accepted all demands of striking cabin crew. This has saddled China Airlines with higher costs and prompted other employee groups to ask for more too.

Two Taiwanese airlines exited the market in 2016: LCC V Air and then its full service owner TransAsia. Their exit is intertwined: by launching a LCC and transferring routes to it, TransAsia deprived both airlines of scale and relevancy, and TransAsia was small to begin with. From a market perspective, TransAsia and V Air will not produce a lasting void. Their exit however was a reminder to airlines to adapt or perish in the rapidly growing and changing market.

The market driving change is necessarily China. Although dynamic, 2016 performed relatively stably. Domestic traffic, despite stories of China's changing economy, remained strong. While air travel demand is generally linked to GDP growth, this link is not so strong in China. Other factors are powerful: infrastructure constraints are holding back demand while route development and visa liberalisation increase demand. A shift towards a consumption economy is good for travel prospects.

The usual challenges - infrastructure, air traffic control, the government's strong influence - remain. What was special in 2016 was that it was marked by a flurry of long haul development as airlines looked to snag the last opportunities under traffic rights.

China had one unexpected development, one that may have profound change on the future of Asian aviation. That is China Eastern's awarding of base rights at the new Beijing airport in Daxing, to open in 2019. It was long assumed China Southern, which has a small base at Beijing Capital Airport, would win the rights to be the home carrier of Daxing Airport. Smaller carriers were mentioned as a possible upset, but China Eastern was not expected.

The result is that China Eastern will be the only Chinese airline with base rights in both of China's two key cities of Beijing and Shanghai. Those rights afford first opportunities, and degrees of protection from others. Dual-hubs impact not just other Chinese airlines but all airlines looking to serve the China market or beyond - Chinese airlines are still yet to ramp up their status as sixth freedom operators.

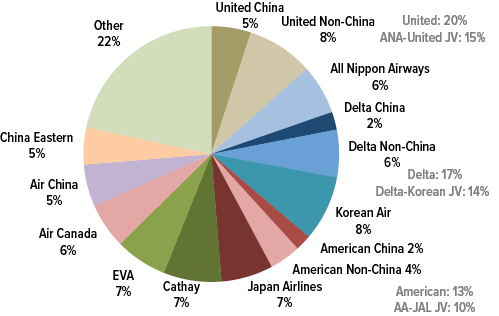

Chinese airline expansion internationally has been particularly challenging for Korean Air, which for years relied on carrying China-North America transfer traffic. A number of other challenges impact Korean Air, too. A JV with Delta now seems possible, and this will help in North America and around Asia.

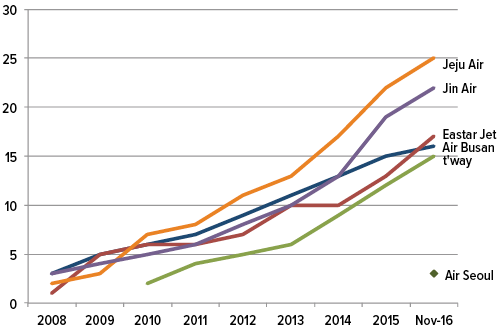

Korea's other major operator Asiana is still struggling to find relevancy and a new CEO, despite solid intentions, is having a hard time changing Asiana's legacy ways. Asiana launched a new LCC, Air Seoul, to narrow its void in the large but increasingly saturated LCC market in Seoul. Other Korean LCCs, including Jeju Air and T'way, are expanding from other Korean cities as they seek new markets. Korea's LCC fleet should reach 100 aircraft around the turn of the year.

The LCC market is fragmented but consolidation is unlikely as Korean LCCs await the massive opportunities that will come from open skies with China. They support that move to liberalisation but influential Korean Air does not. Korean aviation, from the government to main hub at Incheon, will need to evolve from serving Korean Air's interests to achieving a broader strategic goal. The country's LCCs have evolved erratically. As their combined total reaches 100 aircraft, it is time to consider policies to directly support them, and for example what low cost infrastructure should be available at airports.

The clock is ticking in Japan. 2017 will allow the resurgence of Japan Airlines. Following its spectacular Chapter 11-style bankruptcy in 2010, JAL was bailed out and restructured but with handicapping conditions that expire in Apr-2017. While JAL has been preparing towards that date, no one has been more conscious of it than All Nippon Airways, which has been free to expand with unchecked competition.

JAL rightly worries ANA will lobby for the restrictions to be extended. ANA sees that JAL was given unfair advantages in the bailout and the restrictions only partially level the playing field. The real driving thought is that after years of playing second fiddle and fighting for recognition, ANA has become Japan's largest international airline (it has long been the biggest domestically). ANA battled for traffic rights against JAL but has now persevered.

ANA has fundamental advantages. In Japan's tight market JAL's bankruptcy is still a taboo subject and alienated some employees and customers. The government is still aligned to ANA, and ANA has more friends abroad. Being second place has turned out to be an advantage: while JAL rested on its laurels in the 1990s and early 2000s, ANA saw it had to do things differently, and turned to partners. As a result, ANA's JVs in North America (with United) and Europe (Lufthansa) are much stronger and bigger than JAL's JVs (with American and then IAG/Finnair).

ANA may be over estimating the importance of Apr-2017. JAL does have expansion plans, notably its key North American market and then Southeast Asia, where ANA has eclipsed JAL. Southeast Asia is an important market to feed North America, and is a market in its own right that is not (yet) being heavily served by LCCs. Southeast Asia is taking on greater prominence in Japan's rapidly growing inbound tourism, although Northeast Asia continues to define visitor source markets. Japan's tourism urgently needs to diversify towards secondary and regional markets since Tokyo and Osaka do not have enough capacity to meet the government's ambitious tourism goals.

Within Northeast Asia, traffic is being driven by LCCs and mainland Chinese airlines. There is little worth fighting for here, and JAL has exposure via its minority investment in Jetstar Japan.

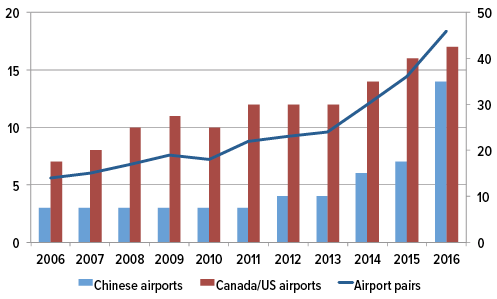

China-North America airport-pairs and number of airports with service: 2006-2016

LCC Jetstar Japan is finally expanding overseas after needing to bed down its domestic operation. ANA-aligned Peach continues its steady and under-stated expansion. Vanilla Air, another ANA vehicle, still awaits direction; its latest foray is fifth freedom international flights. Cross border JV Spring Airlines Japan remains small, focusing on the Japan-China market, while AirAsia Japan Mk II is preparing for an early 2017 launch. Japan's hybrid airlines, dating back to 1990s/2000s, mainly subside on their domestic slots at Haneda. Former independent LCC Skymark, which has resisted strategic alignment with minority owner ANA, also wants to expand internationally.

Faced with this diversity, JAL's main expansion pursuit is likely to be in non-flying business as it shifts from an airline company to an aviation group.

The salvation of Northeast Asian airlines is increasingly a group structure and strategy. Historically, airlines like Korean Air, Asiana and EVA Air have had a group role since they are part of larger conglomerates. But in those examples, the groups span industries other than aviation, and the airline brand is seldom leveraged for the gain of other companies.

ANA has transitioned to ANA Holdings, encompassing not just LCCs and airline investments, but ground-based businesses that are not traditionally sexy yet deliver more consistent, and often higher, profits. ANA has invested in a pilot training academy. Maintenance is another area to pursue. JAL wants to replicate this, investing in airlines (Southeast Asia in particular) and ground-based businesses. Loyalty programmes are important and still not being harvested.

Cathay Pacific has little room for manoeuvre in its flying business. Even in the good times profits were not great. That era for Cathay, as for any high transfer volume airline, depends on the airline being strong in its own right but also in its origin markets being deficient. Cathay's source markets have woken up and clawed back traffic, and in other markets greater competition has emerged.

Then there are Cathay's own, internal problems, including the matter of its "legacy" profile. In May-2016, Cathay chairman John Slosar berated that the term "legacy airline" implied to him an airline without creativity and imagination. "Don't apply it to Cathay Pacific," he said. By Nov-2016 the airline's own magazine made reference to "legacy airlines such as Cathay".

Cathay has indeed become legacy, with some of the most generous terms for employees in the industry, yet routinely squeezed by unions. Its home in Hong Kong is expensive and the government is not fully committed to supporting its aviation hub.

Cathay is heading for a full year loss at the airline level. A poor fuel hedging strategy is incurring losses - but there is more to it. Even without the fuel hedging losses, Cathay has become structurally unsustainable.

In Southeast Asia far-reaching restructurings are occurring at Malaysia Airlines and, to some extent, Thai Airways. Yet no Asian airline has been able to metamorphose as European or American airlines have. Increasing aircraft seating density in economy and reducing premium seating is becoming common. Only Singapore Airlines, Japan Airlines and British Airways are the notable holdouts on 10-abreast 777-300ER economy seating now that Cathay will retrofit to that.

Cathay is not about to give up flying. It is preparing for battle with the long haul expansion of China's HNA Group full service airline Hong Kong Airlines, which together with sister LCC HK Express have picked Cathay's regional routes one by one and lowered yields. Now the long haul pursuit begins. Hong Kong Airlines is emboldened by low fuel prices, restrictions on its HNA sisters that cannot get good traffic rights out of China, and the availability of widebody aircraft as orders and leases dry up or get cancelled. Its expansion may be bolder than originally predicted. This is already being felt by HK Express, which has seen Hong Kong Airlines quickly grow larger than HK Express in the key market of Japan.

Although Cathay fights where it can, it is preparing for a shift away from flying and towards a business model that reduces reliance on flying and leverages the power and affinity of its brand. Asian airlines still have strong and respected brands, unlike in North America and Europe. If Cathay works to commercialise brands outside of selling seats, it might just be an Asian airline that can make it work.

But shareholders may not support a de-emphasis on flying. AirAsia's founder Tony Fernandes told Bloomberg in Nov-2016 that the spin-off of its leasing business, with others to come, is because airline shareholders do not see appropriate value. Shareholders have long been wary of management being distracted from their "core" business. As in the US, this may be a problem not with airlines but shareholders, yet they can have large sway.

Northeast Asia may be different. ANA's shareholders are not so scrupulous while Cathay's main shareholders are Swire and Air China, and so long as those two are aboard, others are not significant.

Many of these moves towards group structures and activities are led by a need to respond to Chinese airline expansion. Yet Chinese airlines are eyeing group structures, too. A government initiative to expand internet businesses is causing Chinese airlines to play more in the space and win back direct distribution. Even more broadly, China Eastern has asked its government for permission to acquire other companies.

The big aviation group globally is HNA, with an expansive investment strategy. The HNA empire is vast, from airlines to hotels to real estate. Within the aviation ecosystem, there are airlines, airports, leasing, catering, etc. Yet synergies, for the time being remain limited. This is a long term play.

For now, it is a buyer's market and HNA is eagerly racing to take opportunities while building up favour in the Chinese government.

Korea LCC fleet: 2008-2016

Some of the speed may be reflective of a concern HNA will be halted, locally or by foreign governments increasingly wary of Chinese investment. HNA may now have become too big to fail; additional investments cement this position and also HNA's evolution to be China's de facto fourth national airline.

Regional Asian traffic has been strong, as consumers stick to reliable markets amidst security concerns in Europe and, to a lesser extent, mixed feelings (gun violence, racism) in America. Australia and New Zealand, another "safe" region, are also benefitting - but perhaps unsustainably. Australia and New Zealand become attractive for airlines looking to re-deploy capacity or which have new aircraft but either saturated North America/Europe or have no further traffic rights.

This means long haul, premium-heavy aircraft are being directed to Australia. Greater China airlines are sending 777s while Korean Air is regularly deploying its A380. Australia is well-served by the A330, but the larger aircraft may not be appropriate. In the long term, this will probably be corrected with some reduction of capacity.

In these conditions, foreign airline strategies are being re-evaluated. United Airlines, the single largest trans-Pacific operator by far, has had a management change resulting in a focus on domestic flying, which United previously had largely considered as feeding international. United has incoming widebodies it will need to deploy, but now it is unclear if United may slow Asia growth. American is looking to grow overall while Delta wants to boost its Los Angeles hub. Air Canada is showing stronger interest in Asia.

Share of trans-pacific market based on seat capacity with hypothetical Korean Air-Delta JV: Nov-2016

The major European airlines are steady in Asia. LOT stands out as does SWISS, which is growing through upgauging of A330s/A340s with 777s. Iberia is now in Asia but bolstered by support from IAG, and in the case of Japan, JVs. LOT's growth is more precarious. The Lufthansa Group, a major force, is bedding down JVs with Singapore Airlines and Air China. AirFrance-KLM, struggling to restructure under dictating unions, plan long term growth that is below global averages.

Qantas, after a restructuring that has lowered costs, is now a more active player. Qantas also needs to deploy widebody aircraft out of the slackening long haul domestic market, and Asia is an easy target. Virgin Australia will follow suit as part of its ownership and proposed partnership with HNA.

Even if there is no expansion in 2017, there is ample capacity overflowing from 2016 (and even earlier) to be absorbed. Although China growth looks to be cooling, after a few years of especially strong over-capacity in international segments, the availability of traffic rights will change the outlook. 2017 will of course see further growth, but much will not be visible until early and mid-2017, reflecting not only market conditions but long term management interest. Yields too will certainly remain pressured.

Even if there is no expansion in 2017, there is ample capacity overflowing from 2016 (and even earlier) to be absorbed. Although China growth looks to be cooling, after a few years of especially strong over-capacity in international segments, the availability of traffic rights will change the outlook. 2017 will of course see further growth, but much will not be visible until early and mid-2017, reflecting not only market conditions but long term management interest. Yields too will certainly remain pressured.

Prospects are not strong for economic gains to vastly improve the demand environment. 2017 should perhaps be the year airlines understand the accelerating growth and eagerness of some airlines - and not just in China - is to remain and continue a shift in the world order. It is little short of global disruption.

At CAPA's Asia Aviation Summit in Singapore in Nov-2016, an informal poll found a majority in the audience believed no major Asian airline would fail by 2020. Yet as always, survival and thriving are two different matters. Even if a future can be secured, a stronger future awaits those who restructure. This will involve more than incremental change internally, as the tectonic plates shift.